Sherri L. Smith & Elizabeth Wein

Sherri L. Smith & Elizabeth Wein

Listen to the Episode

Show notes

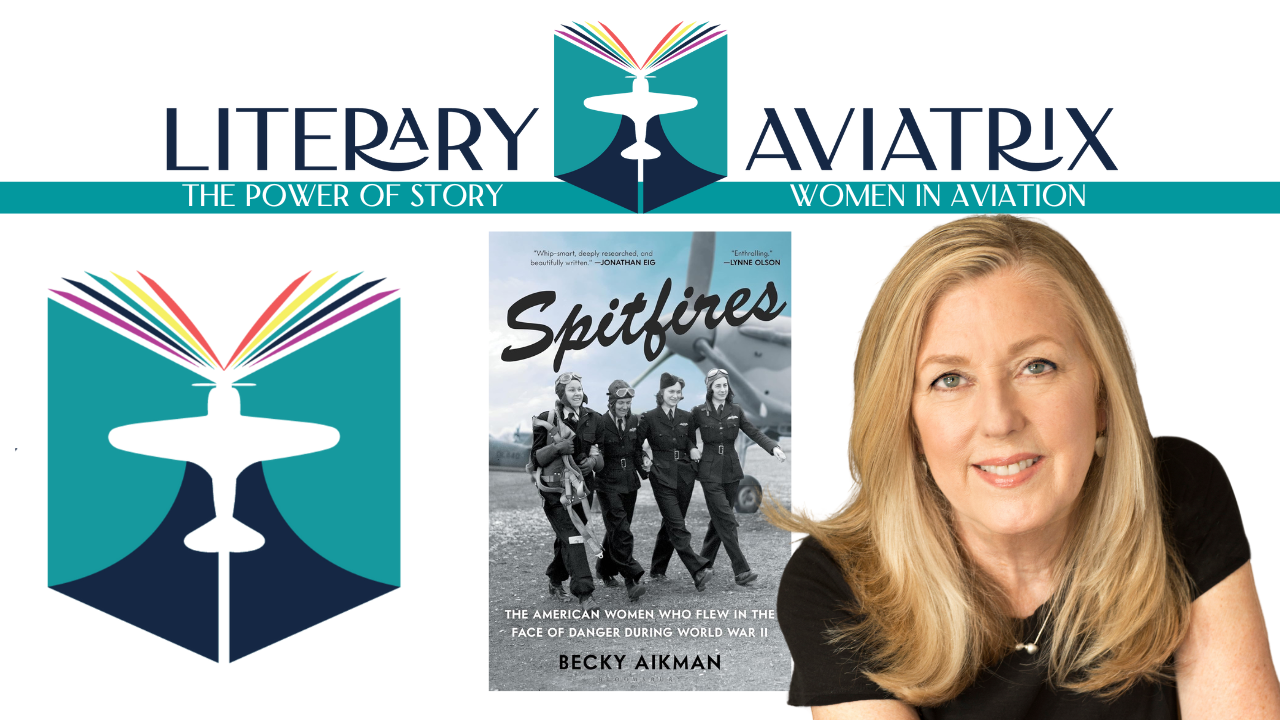

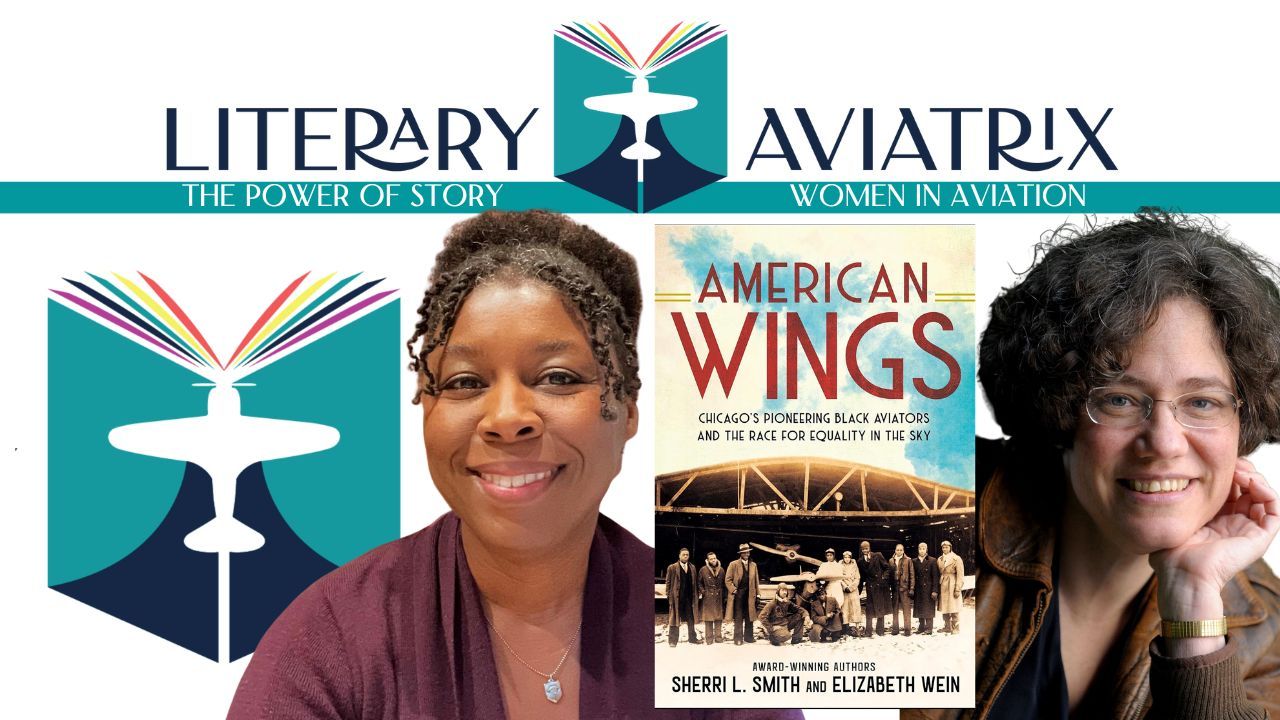

In this interview with all-star award-winning young adult authors Sherri L. Smith and Elizabeth Wein, they discuss their fabulously researched and written young adult non-fiction American Wings: Chicago’s Pioneering Black Aviators and the Race for Equality in the Sky, and give us a glimpse into this fascinating aviation history and the process that brought it to life. This book is essential reading for any avgeek or aviation history buff!

Transcript:

[00:00:00] Liz: Hello and welcome. I’m Liz Booker and I’m thrilled to host the co authors of an exciting new book, American Wings, Chicago’s Pioneering Black Aviators and the Race for Equality in the Sky.

Intro:

Fewer than 10 percent of pilots and aircraft mechanics are women. These are their stories of tenacity, adventure, and courage.

Stories with the power to inspire, heal, and connect.

Welcome to the Literary Aviatrix Community, where we leverage the power of story to build and celebrate our community and inspire the next generation of aviation.

Sherri L. Smith, welcome back.

[00:00:46] Sherri: Thank you. It’s exciting to be here.

[00:00:50] Liz: It is so exciting to have you. And Elizabeth Wein, welcome back.

[00:00:53] Elizabeth: Thank you. You do the best work.

[00:00:55] Liz: Oh my gosh. Oh you both do the best work, which is something that I’ve been gushing about all over social media, that you two especially came together to tell this amazing and impressive history that just seems to have been buried in the crevices up until this book.

For those of us, so I had the pleasure, the very distinct honor of being able to interview both of you during my first season, so people can go back to those interviews on the website or on the podcast and hear in-depth about your other work and your careers and those kinds of things.

But just very briefly, we’ll start with Sherri. Can you just give us a framework of what brings you to this story?

[00:01:37] Sherri: The short answer is Elizabeth Wein brings me to this story. That and my I guess a couple of my previous books Fly Girl. Is about a light skinned Black girl who passes for white to join the Women’s Air Force Service pilots in World War II.

And at the beginning of that book, her dream is to get her pilot’s license from a school in Chicago that is known to be run by and willing to teach African Americans the Coffey flying school. And, That was based, in fact, on a guy named Cornelius Coffey. So, I had written about that and then when I wrote a non-fiction book called Who Were the Tuskegee Airmen?

I included a sidebar about Coffey because he was instrumental in training a lot of people who went on to be instructors for the Tuskegee Airmen. And then I wrote another World War II aviation book. It’s a bug of mine called The Blossom and the Firefly. And it’s World War II Japan.

But when we were talking about dream authors to get a jacket blurb from, Elizabeth Wien’s name came up and we reached out to her and I’d known—I’d never met Elizabeth before, but when Fly Girl came out, everybody would say to me, oh, have you read Code Name Verity by Elizabeth Wein? It’s amazing.

Which was cool, but she was like the Ferris Bueller and I was the sister. I was like yeah. Everybody loves Ferris . What about what about my book? What about me? When we reached out to Elizabeth, I was like, Sherri, get over it. You need Ferris’s approval for your book.

And then—you didn’t know you were Ferris Bueller, did you? And then my editor comes back to me and she’s Elizabeth says she’ll give you a blurb, but she wants to talk to you. And I just. I thought, okay, it’s going to be a street fight or something. I don’t know what’s going to happen. And instead it was, would you be interested in writing this book with me?

[00:03:47] Liz: Oh, Sherri, that’s such a great story. Elizabeth, how about you? Tell us about your background and then how you decided to pick Sherri.

[00:03:52] Elizabeth: So I am, World War II fiction is also my thing. And that is because I got a pilot’s license in 2003, which is longer ago than I like to admit, because I’m still very much a baby pilot.

But before that I wrote historical fantasy. And once I started to fly, I just wanted to write about flying. And I was pretty much the only civilian woman on my airfield who was taking flying lessons. I was in my thirties. And I was baffled by the lack of other women in light aviation, where I was learning to fly here in Scotland, which is where I live.

And I became, that’s what got me interested in women in aviation. I just started like looking around to see what the history was and who the firsts were. And it was through that, that I started uncovering other, as it were, minority aviators. Women were so scarce that they tended to crop up with other people who were scarce in early aviation.

And that’s how I discovered Cornelius Coffey and his crew. And John C. Robinson, who he worked with in the early part of his aviation career, was a very interesting guy who ended up going to Ethiopia and flying for Haile Selassie when the Italians were invading Ethiopia in 1935, ‘36. And I actually included Johnnie Robinson as a fictional character under a different name in my novel, Black Dove, White Raven.

And I also, in that book, gave a nod to the Coffey Flying School. The kid who is the, one of the two main characters in that book ends up there at the end of the, at the end of the book. So I knew about them. I knew about the Tuskegee Airmen because I discovered them when I was writing Code Name Verity and I wanted to include a Black airman in, right at the end of that and like a cameo role and discovered that I couldn’t use an American because they weren’t flying the right kinds of planes, and they weren’t flying in integrated units. So I used a Caribbean man.

But, I knew about these people as well, and I’ve read Fly Girl, and I loved Fly Girl, and I have had people say to me, Oh, you wrote Code Name Verity! Have you read Fly Girl? So it does cut both ways.

And when Sherri’s agent sent me The Blossom and the Firefly, I, or was it your editor who sent that to me? It doesn’t matter. Your editor sent me The Blossom and the Firefly. And I read it, and it was also wonderful. And I thought, huh, this woman, she’s written about the Tuskegee aviators. She knows who Cornelius Coffey is. She does fantastic historical research. She writes about World War II and flying.

Our paths have not really crossed, but they are paralleling each other. And I had just finished, I had just published a nonfiction book about aviators called A Thousand Sisters, about the Soviet women who flew combat missions in World War II. And that had been a boatload of hard work. And I thought, I really want to write about these people in Chicago, but I don’t want to do it alone.

And Sherri just seemed like the obvious person to ask. And having her reach out at exactly that moment when I was kicking around looking for a new nonfiction topic was it was, serendipitous.

[00:07:58] Sherri: That was the word I was going to use, see? Thank you. That’s why we can write together.

[00:08:03] Elizabeth: We do this a lot, yes.We finish each other’s sentences.

[00:08:05] Liz: Oh, that’s adorable. That’s adorable. Oh my gosh. I can’t wait to hear I, I got, so I had the privilege of seeing you on tour recently. You were doing a pretty hard press at schools in California. And I think I got you on the tail end of that the last night that you were there at Vroman’s bookstore in Pasadena.

And I was just sat up right in the front like the fangirl that I am. And I loved everything that you guys did in sharing both the history that I want you to talk about here, but also talking about the writing process. But so like you’ve already dropped the names, Cornelius Coffey, at least the men’s names so far.

So I’m just going to stay out of your way. You guys did such a good job and kind of honed this storytelling so well and worked so well off of each other. I’m going to stay out of your way. And if I have a question, I’ll jump in, but take it away, ladies. Tell us about this book.

[00:08:59] Elizabeth: Okay. So we mentioned the men’s names.

We didn’t mention the women’s names, but obviously they came up at the same time, when I was doing my fooling around looking for people, and they came up also because women were so unusual flying. In the early days. I want to say it was more normal for women to fly in the 1930s than it is now.

But you had to go back to find them. And of course it was extremely unusual for a Black woman to be flying. And I don’t know if we’ve made it clear, but all these aviators that we’re talking about are Black. And, Willa Brown, who worked with Coffey at his flying school and pretty much ran the place from an administrative point of view for years and years.

She just fascinated me. She was the first Black woman to get a federal private pilot’s license in the USA. She was the first Black woman to get a limited commercial license. She was the first Black woman to hold an office in the civil air patrol. So she, she did all these amazing things.

And we hear a lot about Bessie Coleman. Now we hear a lot about Bessie Coleman, who was the first Black woman to get an international pilot’s license. And indeed, the first Black woman to get a license. And the trials and tribulations that she had to go through in order to do that. But we don’t hear about anybody who came after her.

And she actually inspired a ton of people. So she inspired our aviators. Sherri, why don’t you take it from there?

[00:10:43] Sherri: The story, the nonfiction books always have these incredibly long subtitles. To explain what they are. So our book is American Wings, Chicago’s Pioneering Black Aviators in the Race for Equality in the Sky.

And so while most of the story is set in Chicago, it is it starts with our young people who we focus on four people. So Cornelius Coffey, John C. Robinson, the incredible Willa Brown, and another woman named Janet Harmon Waterford, later Janet Harman Bragg, when she remarries and Janet’s sort of an interesting personality because she was a nurse and she just, she had a good job.

She moved to Chicago and had some money in her pocket and saw a billboard that said, “Birds learn to fly, why can’t you?” And that set her off on the quest to learn how to fly, but where this story starts is really, we’re in the heart of the great migration. Cornelius Coffey was born in Arkansas, and when he was young, his mom died, and he moves to Omaha, Nebraska.

And when he is a young man, he, when he’s like a teen, a young teen, he gets the chance to fly with a barnstormer, in a farm field somewhere and the guy is a white World War I vet who decides he’s going to scare the crap out of this little Black kid because the military and the United States in general did not believe that African Americans were brave enough or smart enough to serve honorably in the military as a soldier, or have the wits to fly, despite the fact that Bessie Coleman was doing it in 1924, despite the fact that Eugene Bullard did it in World War I in France. The difference is they both had to leave the country to do it.

It’s amazing if people don’t believe in you what you cannot do. And so it’s also equally amazing if you believe in yourself what you can figure out and go do it anyway. I feel like it’s a bit like Dumbo with that magic feather, you need something to hold onto and so Eugene Bullard became Bessie Coleman’s magic feather. Bessie Coleman became Cornelius Coffey and John C. Robinson and Willa Brown’s and Janet Harmon Bragg’s magic feather and then they became the feather for other people until people didn’t need it anymore.

And so Coffey, he doesn’t see a future for himself in aviation because the world’s against it. So he becomes a, an auto mechanic and he’s working in Detroit when he has a client Dr. Ocean Sweet, has this amazing luxury car that breaks down on the wrong side of town and Dr. Sweet has it towed to a nearby garage and tells the mechanic on duty there, do not touch my car. I’ve got a guy and he’s going to come and work his magic. And that pisses off the mechanic on duty who happens to be John C. Robinson.

So Coffey comes in and Johnny, I like to think of him as the, the fighting Irish Leprechaun for Notre Dame with the fists up and the hat at the rakish angle, I can imagine Johnny like that. Who do you think you are? And…

[00:14:10] Elizabeth: There is precedent for imagining Johnny like this.

[00:14:11] Sherri: That is true. There’s, on the historical record the man was not afraid to throw a punch. If he felt it was required. But that it didn’t come to fisticuffs. Instead, there was a conversation had because they’d both spent time in Chicago. Coffey had to go to Chicago to learn to be an auto mechanic because he couldn’t find a school that would teach him elsewhere as a Black man.

And, and Johnny had gone to school at the Tuskegee Institute, and but they’d both been through Chicago, and Johnny was headed back, and he said when they realized they both had an interest in flying, he said, look me up if you ever come back to Chicago, and let’s see what we can work out, and thus history was made.

Coffey came back. He actually helped Johnny get a job working at a car dealership where he worked as a, as the head mechanic. And they start applying for flight schools and nobody will take them. And then they have the idea to not check the box that says they’re colored. And they get in on their own merits, but the day they go in to sign up for classes in person, it’s very clear that they are two Negro men, and this school’s we don’t take Negroes, we have too many Southern, white Southern students who wouldn’t want to be in a class with you, and they tried to give them their money back.

And they refuse, they’re like determined to get into this class, and they go about it in two different ways. Coffey goes to his boss. He mentions Oh they’ve got our money, but they won’t let us take the class. And his boss says, don’t take that money back. I’m going to call a lawyer. They need to accept you.

And meanwhile, Johnny…

[00:15:55] Elizabeth: Meanwhile, Johnny who really all his life has a very good image of himself. He’s like, right, I’m going to get into this school, whatever way. And actually says he also has a degree in, in auto mechanics from Tuskegee Institute. As they’re leaving the office of the school, he notices a sign, probably handwritten sign that says that they’re looking for a janitor.

So he thinks, well, you know, they’re not going to take a Black man as a student. Maybe they’ll take him as a janitor. And he went back in, applied for the job and he got it. So for the next several months, Johnny would time his working in the school so that he was basically auditing some of the ground school classes and he’d stand in the back and he’d push his broom and he’d wait afterwards and copy down diagrams from the blackboard and he’d fish paper out of the trash can and check it out and he was reading presumably the same kind of texts that these guys were, that the students were actually reading and the instructor of this class who was a man named Jack Snyder and also World War One Flying Ace, veteran pilot, noticed him, was aware of him, and was sympathetic to him.

So he would ask people, he would ask people a question, and if they couldn’t answer it, he’d turn to the guy in the back with the broom and say, Mr. Robinson, do you have anything you’d like to add? And Johnny would usually know the answer.

And, in the meantime, Johnny and Coffey were actually working on their own to learn all they could about aviation. So they had founded a club, basically a social club, that they called the Brown Eagle Study Group. And they would get together on weekends, and they’d talk about aviation, and they’d read books, and they’d discuss what they read.

And they also were building a kit plane. They bought a Heath Parasol.. Aircraft, which is a one seater with a high wing. And they put this thing together with a Henderson motorcycle engine to fly it with. And neither one had ever flown a plane or had ever taken any kind of a flying lesson, but they put this plane together and eventually it they’ve done all the tinkering that they could and they thought it might actually fly, but how are we going to find out? So Johnny went to Jack Snyder, the instructor, and said, we’ve got this plane, would you mind coming and taking a look at it?

And it was kind of a big deal. They had to they were working on it in a garage and they had to lift it onto a flatbed truck and take it out to a field that would be appropriate for taxiing around in. And so the whole Brown Eagle Aero club turned out and Jack Snyder came along and gets into this plane, starts the engine.

Wait a minute, this is a motorcycle engine. Okay. Starts the engine, taxis around, and sure enough, after a while, suddenly he takes off, and the plane lifts off the grass field and he flies it very confidently around circles, comes back down to land. And so everybody’s thrilled and Snyder goes back to the director of the school and says, look, these guys have built their own plane.

They know what they’re doing. If we don’t teach them to fly, they’re going to teach themselves. We need to accept them. And the director of the school says, well, we might as well take them in because one of them is suing us anyway. That’s how they end up taking classes. And they enroll. They graduate the following year with their aviation mechanics degrees.

They’re, both of them, top of the class. And at the graduation ceremony, the director of the school says to them, You guys have done a great job, and if upi know other Black people who want to learn to fly, we are willing to give you a class of your own. You can teach. And if you find them, the class is yours.

And that is how they Sherri, remind me what the name of the school was. Curtis Wright School of Aviation.

[00:20:41] Sherri: Yeah. The school’s name changed midstream there too.

[00:20:47] Elizabeth: But they began to call themselves. Aeronautical University.

[00:20:51] Sherri: Right, as if they were the only one, but they they start this class and they were telling all their friends, everybody in their club because it hadn’t been easy for them.

The school said you can join this class Coffey and Johnny, but if you have any problems with the students, you’re on your own. And so they had problems with other students who would block them from getting to the vending machine at snack time and try to prevent them from getting the good tools.

And until their teacher Jack Snyder said these guys already have a plane and they are basically, they know everything you’re going to wish you knew, by the time the test comes around. So if I were you, I’d be nicer to them. And suddenly everybody was very nice to them and buying them coffee and snacks.

And they start this class and hopefully there’ll be an even playing field now, right? It’s all African American students all men, except for little Janet Harmon Bragg, the only woman in that first class. And now let’s talk about the intersectionality of minorities and of mistreatment.

Now she’s getting the same bum rush that they had gotten from the white students, people talking down to her because she’s just a pretty little lady and what does she know? And she doesn’t know a wrench from a screwdriver. That was never something in her upbringing. But she had been a tomboy and she was good at math.

She taught herself to drive her dad’s car when she was like 10. That’s something that like, I think at least three of our main characters have in common. Is that they taught themselves how to drive cars when they were like under the age of 12. Yeah.

[00:22:37] Elizabeth: Yeah.

[00:22:38] Sherri: But she but what she had was determination, a good head on her shoulders, and money.

And so she, when they wouldn’t share the good tools, she went out and bought herself the shiniest toolbox and the nicest set of tools at Sears. And then they were all like, could I borrow yours? And she’d say, no. And she one night Amelia Earhart visited the school. And she came through their class and spoke to Janet.

And Janet said this is tough. And Amelia said, that’s the way it’s going to be for a woman, but stick with it. And she did. And that opened up to more women coming.

[00:23:18] Elizabeth: Yeah, they did. They did have several women who graduated from the class and we focused on Willa Brown and Janet Bragg, but they had several others over the years who did graduate from that class.

I was going to say, we’ve been talking aviation mechanics. We haven’t at all been talking about how they actually learned to fly and Coffey and Johnny were by this time getting flying lessons from some white aviators here and there, there were, they did find people that would be willing to teach them, and they were mostly flying from an airfield called Acres, which was run by some white people, and they were, they’d been hanging out there for a long time, even before they had actually joined the class.

And that airfield was scheduled to be sold and turned into housing. Yeah, it was sold. And so they had, they were hunting around for a new place to fly from. And they hit on the idea of building their own airfield. They approached the mayor of Robbins, Illinois, which was a village that was incorporated as an all-Black village.

So it had its own policemen, its own firemen. The mayor was Black and they negotiated to rent a field from them, which they were going to then clear of brush and turn into an airfield and Janet was their financer. She was the one, she was still the one with the steady job. She was the money. She bought her own plane.

They had they all, they’d moved up at this point. Coffey did a lot on his own plane. He did a lot of exchanging of his abilities for aircraft and engines he’d offer to fix something for someone and they would give him an engine and he would then fix it up and install it in a plane that needed one.

So he actually had his own plane at this point, which they were all flying and none of them had enough credentials, flight credentials to teach, but Johnny eventually he was the first one of the bunch to get his license and you could teach not for pay. So he was always a little bit operating on the kind of like the shady side of things as long as it wasn’t technically illegal, he’d do it.

[00:25:54] Sherri: He’d teach you for tips. Find some other way. An honorarium. Yeah…

[00:26:02] Elizabeth: So he was so they basically built this airfield themselves at the stories of their clearing the ground. Janet said the weeds were higher than I was. They had a boulder in the middle of the field that they could not move.

They dug and dug and dug trying to get it out and they couldn’t move it. And eventually they dug a hole around it and just rolled it in, dropped it in and covered it up. The truck that they were using to haul cinders and timber, they built their own hanger as well, you often would only go in reverse.

Everything that they did, this was during the depression, everything they did was made up and was people helping out and they got a lot of help from the village itself who were very enthusiastic about them being there. The hangar that they built was designed by Johnny, who drew up the blueprints for it, and, they could only work on it when he was there because his handwriting was so awful. And then again when they got the, when they got the airfield going and they were ready to fly, because he was the only one who actually had a license, he hogged the flying. So they’d wait and wait all day, waiting for a chance to go up, and then Johnny would go up.

And he was the airport manager he was the guy who, he was, at this time, he was the front man. You know, as we were writing, as we were researching these people and working on them, initially, we divided them up. I said I wanted to write about, this, I was the one, I was the one who spearheaded this idea, I was like, I’m going to write about the people I want to write about, and I said, I’m going to research Johnny and Willa, and you can research Coffey and Janet, and we found as we were working on them, that we became team Coffey and team Johnny, because they told different stories.

[00:28:09] Sherri: They were different personalities. They’re such different personalities, Coffey was very quiet and unassuming. And Johnny was flashy and brash.

[00:28:19] Elizabeth: Yeah. Yeah. And what happened over the years and we chose these four people because they clearly were interconnected. But what happened over the years is that there was a Johnny-Coffey split and it’s not real obvious why that happened.

But interestingly, when it happened, Willa, who became part of their team, because she was enticed by Johnny’s terms, we think, Willa actually ended up working with Coffey and indeed even married to him and Janet did not participate in the school that Coffey and Willa operated, but she did support Johnny in other endeavors.

There doesn’t seem to be. There doesn’t seem to have been a romantic relationship between some people suggest that there was a romantic relationship between Willa and Johnny, but he doesn’t seem to have actually been involved with any of the women that, that we have written about.

[00:29:22] Sherri: I would assume that there was a network of women going, watch out for that Johnny Robinson, you know?

[00:29:30] Elizabeth: There’s this lovely page. They both have, Coffey and Johnny, apart from Willa, who we know that Coffey was married to, both have very elusive wives and, one of the women that Johnny seems to have been married to, there’s a picture of her in the Chicago Defender, the Black newspaper, that reports all these things, which gave us a lot of the information that, that we drew on. There’s a picture of this woman whose name is Ernese Tate and Johnny, and they’re standing beneath the wing of an airplane. And they’re grinning at each other. It’s like 1932, during the time when they were all taking flying lessons and they were building this airfield.

And he apparently is teaching her to fly.

[00:30:17] Sherri: And it’s a saucy caption too. It’s it implies that it’s a flirtation.

[00:30:21] Elizabeth: Yeah, it says something like Johnny, the way he’s looking at her implies that he’s enjoying more than just teaching her to fly. It’s something like that.

[00:30:33] Liz: Those were all of the captions that had anything to do with women at the time.

[00:30:36] Sherri: Interestingly, so Willa ends up married to Coffey, which is surprising, right? You’ve got you could go with Hercules or you could go with the guy holding the reins of the horse or whatever she goes with but it’s very possible that it was completely business related.

They were running this flying school together at this time and spending all their time at the airfield and she wanted to be there and the only like Coffey was living in a trailer there so he could be there 24-7. If she wanted to live in that trailer too, she had to be married because otherwise it would be frowned upon by society.

And so it might have been strictly business. I wish to God we could know like what was that like? Because also none of our four heroes ever had children. They never had children of their own. And so while they might have family members, in fact, we actually just had the privilege of meeting Cornelius Coffey’s grandnephew.

But other than secondary relatives yeah, there’s nobody to say that oh yeah, mom and dad, this or that. And yeah, and Coffey has a mysterious possible first wife, that was one of the surprising things we learned at least I learned in doing the research, is when you live in Chicago just down the lake shore is Indiana, and there is a town in Indiana that was like the Gretna Green of the Midwest.

It was the Vegas of the Midwest. You would get on a party boat and go drink and get married, at this town in Indiana, so that you could have full marital privileges, and then you would go back to Chicago on Sunday or Monday and get divorced. And yeah, so now I question anybody who got married in certain counties of India, like at a certain time period.

Apparently it was such a gimmick that there was a justice of the peace who was bedridden. He had a man down at the docks bringing couples into his bedroom so he could marry them. Isn’t that funny? And it ended when the judges in Chicago complained. They’re like, we’re tired of processing all these divorces.

[00:32:58] Elizabeth: Yeah, so this is we went down a lot of rabbit holes like this. Both of us, I think, spent a lot of time trying to chase down the mysterious spouses of these people. And you kept finding out these like bizarre local rules and things that people took for granted at the time and yeah, I don’t know if we’ve been telling, we’ve been telling a chronological story but

[00:33:29] Liz: So let’s back it up a little bit about the ladies and I think you talked a little bit about Janet but a little bit more about Willa Brown and how she came to aviation.

[00:33:39] Elizabeth:

We didn’t do that yet because we were still back at Robbins at the airfield that these guys built. And. That didn’t actually last very long it, after they’ve been flying there for about a year and a half, and there was a windstorm, there’s actually a tornado, although it didn’t come through Robbins, but the high winds that day took down the hangar that they’d built, and that Johnny had designed, and threw their planes everywhere and really trashed two of them. Janet’s plane, they were able to repair, but it wasn’t flyable immediately. And they basically started looking for a new place to fly. And where they ended up was a place called Harlem Airfield, which is not in Harlem, New York, it’s in Harlem, Chicago.

It’s in what’s the name of the actual town? Harvey? No, it’s not Harvey. It’s what, it’s one of these little towns that’s now been subsumed in the Chicago-ish suburbs, and it was at the corner of Harlem and 87th Street, I think. And so there was, it was also run by a white guy who said to them they, they encountered him in some of their flying before, and he said, yeah, come on.

Your field is no longer flyable. You can fly from our field. You can fly from the other end of the runway. You won’t mix with the other guys. Yeah, the other white guys. So that they did have trouble. Getting along there as well the hang, the hangar that they had been given mysteriously burned down, the airfield owner built them another hangar, but eventually things settled down there and actually settled down enough that they started having integrated air shows.

That were sponsored by the airport managers there, quite possibly the first ones of their kind, which were very well attended. There are thousands of people, mixed audiences coming to watch and men and women participating, Black and white participating.

[00:35:56] Liz: This is important that we hear about when we hear about Bessie Coleman, because I think there were times when she was not going to be allowed to perform in front of Black audiences and she wasn’t having it.

Is that true?

[00:36:07] Elizabeth: That that is true. That was 10 years earlier as well. So the fact that they didn’t have to fight. Yeah. She had blazed that trail. So Willa was she had a degree in business administration. She lived in Gary, Indiana. And she was teaching at a high school there.

She was teaching business at a high school there, and she eventually moved to Chicago and was involved with another teacher. She may or may not have been engaged to him, and in any case, they were going steady, and she took him home with her to meet her parents for Mother’s Day, and on the way back to Chicago, they were both involved in a terrible car accident, which killed him, and Willa may have been driving, but she was also very badly injured, and it was in the aftermath of this accident that she was not really doing the work, not capable in body and maybe not in spirit either of doing the work that she had been doing.

She’s working at a lunch counter, which happened to be the place where the now calling themselves the Challenger Aero Club, Coffey and his crowd were hanging out when they were not flying. And she overheard them talking. She started chatting to them. Johnny Robinson put the moves on her, probably. And he said why don’t you come out and join us?

And I can teach you to fly. And so she did go out and join them. And he did probably give her first flying lessons. And she also enrolled at aeronautical university and got an aviation—I think that was another one of her first. No, Janet must have finished her degree before. Yeah. Yeah.

[00:38:10] Sherri: She was the secret sauce, I think, to our group because she like Johnny, she had a flair for showmanship.

But she also had business acumen that I would say none of them had. And she knew how to drum up business when they started their air shows. It was her idea. She put on her white flying jodhpurs and her full flying kit. And stormed the offices of the Chicago Defender.

And she was beautiful. She looked like Lena Horne and she went in there, hands on, did the Wonder Woman stance and is like, I want to talk to someone about our flying club. And the male reporters fell over themselves to be the one she spoke to and Enoch Waters won and she sat down with him and explained what they were doing and he had no idea that there were Black aviators in Chicago and he started a whole movement with the newspaper to support their endeavors and spread the word because there was like a Black newspaper wire, like the Associated Press. And so these stories would then go out across the country about what was happening in Chicago.

[00:39:25] Elizabeth: So he also, he was the guy who came up with the idea for them to nationalize their organization. And the reason he did that was because his publisher, who indeed was Robert S. Abbott, the guy who’d sponsored Bessie Coleman to go and do her flying in France, the publisher couldn’t quite justify giving these guys free advertising, as it were, but if they were a national organization, he could because they were then promoting, aviation throughout the United States and aviation for Black people throughout the United States,

[00:40:03] Sherri: And Abbot had a real desire to uplift the race by spreading word of good and amazing, impressive deeds.

[00:40:11] Elizabeth: And the timing of this was really a perfect storm because now we’re edging to the end of the 1930s. The National Air Airmen’s Association of America was founded in 1939. You will the date of World War II. It’s also the beginning of World War Two in Europe 1939.

And the U. S. of course, was very much aware that it might end up at war. Now, they didn’t want to be at war. They had neutrality acts in effect. They were doing their darndest not to get involved with Europe’s problems, but they knew that they might end up going to war and looking toward the future with that in mind.

There were a couple of aviation bills that were being put forward in Congress, and one of them was to create the civilian pilot training program, which would basically provide government funded pilot training to licensed to the stage of being licensed. So you would have a private pilot’s license at the end of it, and therefore they would create a whole bunch of jobs for people to become instructors for more planes to be built, and they would have a core of people who were ready to be trained to be combat pilots should the country go to war. Now, the civilian pilot training program had no, there was nothing in it that guaranteed that Black pilots would be included in the program.

And so our group basically with using the national oh, God, what are they called? National Airmen’s Association of America using that as their front, they started lobbying to have something included in this bill that would guarantee that Black people would also be able to fly.

[00:42:20] Sherri: They were lobbying earlier than 1939. I think they started in thirty-f. . .

[00:42:25] Elizabeth: They were. They were lobbying before that. The program was a sort of basic version of the program was rolled out in 1938. Which had one Black aviator involved in it, and that was because he was already enrolled at a school that had a flight program.

It was a white school that had a flight program, but there was nothing in it to guarantee that there would ever be any more. So they were lobbying before that. But in May of 1939, they decided as a big gesture they would hit the halls of Washington themselves. And they called this was going to be a Goodwill flight.

Two of their number, Chauncey Spencer and Dale White, were going to participate and they were going to fly from Chicago to Washington. And this, I can’t emphasize what a big deal it was to make that kind of a flight in those days. It was going to take them. Several days if they went straight there, and they weren’t planning to go straight there.

They were going to stop at colleges and flying clubs along the way and talk to people and help drum up some support for these bills. So off they went. They got a lot of press coverage.

[00:43:57] Sherri: Not that easy. They had to rent a plane. They had to get a plane first.

[00:44:03] Elizabeth: They were reset. Oh yeah, that’s true. They had to raise money first. Sorry, I keep trying to jump ahead and I forget about all the nothing is ever easy. All the joy that went into it.

[00:44:20] Sherri: Nothing is ever easy. So they were fundraising to rent a plane and they still didn’t have enough money. And Chauncey Spencer’s crying about it at work one day and one of the women said why don’t you ask the Jones brothers who were they were policymakers, which is basically gambling.

They ran like this lottery like system in the Black neighborhood of Chicago known as Bronzeville. And they also ran a department store. And so he went down to the department store, hat in hand and the Jones brothers, these low level gangsters basically, gave them the money, gave them an extra thousand dollars to go do the thing, and they thanked them later on by flying over their house and dropping flowers on the doorstep from an airplane to say thank you. But so they raised the money. They rent this plane that is not the best plane in the world. It is the plane that they can afford.

Which means that they have a big fanfare they take off and they break down in Indiana a state away. Yeah. Coffey and another guy have to drive out with the piece that needs to be repaired. The townspeople, this white township is like, who are these Black men fell from the sky?

Who are these people? But they put them up and took good care of them. They get their plane repaired, and they plan on coming back to that town one day and putting on an air show, which they do, to thank the people for their good care. By hook or by crook, they’ve got no lights on this plane. They but they’re running behind schedule.

They’re forced to land in the dark by following another plane, which, of course, is dangerous and illegal, and they almost get thrown in jail for that.

[00:45:55] Elizabeth: Actually, the reason that they end up flying at night in the dark is because when they landed in Morgantown, West Virginia…

[00:45:58] Sherri: That says it all, West Virginia…

[00:46:02] Elizabeth: The people at the airport there said, now you can’t stay here. It’s not on record where they said, you’re Black, you can’t stay here, but that was certainly the implication. And they made them take off again, despite the fact that they had no lights. They popped into Pennsylvania, where they were then held up for not landing legally. And they got bailed out of by the editor of the . . .

[00:46:23] Sherri: local eBlack paper. Pittsburgh Courier.

[00:46:26] Elizabeth: Another Black paper who also gave them another chunk of money to keep them going.

[00:46:32] Liz: Yeah, I’m so impressed by these. I’ll be honest, I didn’t know that history. What brought me to it was our friend Carole Hobson’s book about Bessie Coleman and just the importance of the Black newspapers at the time and the network that they established. They’re pretty incredible. Yeah.

[00:46:46] Sherri: Yeah. They really did. Yeah. The, the triumphant ending of this this Odyssey to DC is that they get there, and they have a contingent of people that they’re meeting with and they are, underneath the Capitol building, there is like a little railway station, a little subway.

[00:47:07] Elizabeth: This was one of the things, this was one of the rabbit holes that I thought was so dang cool. It was built in 1909. An electric subway system beneath the Capitol building.

[00:47:17] Sherri: Just to take you from one end to the other for votes quickly. And they’re walking down there, and who should be coming the other way but a young senator from Missouri named Harry S. Truman. And so they’re trying to tell everybody who they can please vote to put Black schools into this program. And he’s interested in what they’re doing. And he says, can I see your plane? And they are like, absolutely. And so he goes out to the airfield and he takes a look at this plane that has been clearly stuck together with gum and tape.

And he says, if you guys are brave enough to fly that thing, I’m brave enough to try to help you get what you want. And he does. And that was a relationship that had great significance for the whole nation because after World War II in 1948, Harry S. Truman is the president who desegregates the United States military.

[00:48:14] Liz: And then it also leads to the Tuskegees, right? To the Airmen who actually went off to World War II.

[00:48:20] Elizabeth: Yes, so the civilian pilot training program, there were thousands of schools across the United States that were involved in it, so they’re all being given federal funding to do this pilot training and there were six Black colleges and the Coffey school of aviation, which was not associated with a college that they were kind of treated as an experiment the whole way through, but they threw out the existence of the civilian pilot training program.

Including when the nation went to war and it became the war training service, the Coffey school was being given funded and involved in pilot training. And eventually they were training pilots who would go on Tuskegee. They had a very stormy relationship with Tuskegee, which is partly responsible, I think, for the rift between Johnny and Coffey.

Johnny was a Tuskegee alum, and throughout the 1930s, and this is like a part of the, a thread of the story that we haven’t actually touched on in this talk, but which we do touch on in the book throughout the 1930s. Tuskegee was thinking about an aviation program.

[00:49:44] Sherri: They really weren’t thinking about an aviation program until Johnny said, You should think about an aviation program.

And they pooh poohed it. And then…

[00:49:50] Elizabeth: They didn’t pooh it. They didn’t pooh it.

[00:49:53] Sherri: In the very beginning, they pooh poohed it.

[00:49:57] Elizabeth: They were just like, they were like, Yeah maybe.

[00:50:00] Sherri: It seemed like a fad.

[00:50:02] Elizabeth: They kept saying, come to Tuskegee, Johnny, and teach this aviation program. And he kept saying, after I do this other fancy thing.

He went off to Ethiopia.

And they said, no, we’ll hold your job for you. We’ll hold your job for you. And then he came back and they said, now are you going to, now are you going to teach your aviation program? He goes, no, now I want to open the John Robinson School of Aviation. He wanted And I want you to sponsor it. That’s not our plan.

[00:50:28] Sherri: He wanted more money. He wanted more fame. And they wouldn’t give it to him. But the real thing is he and Coffey and another guy flew down in two planes. They were gonna go to Tuskegee for a, an alumni event and be like, Ta da! This is what aviation can be for Black people. And Johnny is rather pig-headed and not listening to Coffey.

And so he ends up wrecking their plane. And so Coffey and who was flying with them in the Bullpup I can’t remember his name, but the other fellow who was with them, they end up giving him, the other guy’s little plane to make it to Tuskegee late, while they’re stuck in this town waiting to repair their own plane, and pay for the damage to the field that they crashed in, and so Johnny gets down there, and it’s funny, Coffey was like we never did convince Tuskegee to like, do a flying thing with us. And maybe we would have if we hadn’t crashed that plane.

So Johnny was pretty brash and they weren’t interested. And then Tuskegee is in Alabama and it’s a southern school Coffey and Johnny and them were all about integration and Tuskegee was not. And so what happened was when they were lobbying for who would get when they finally the Tuskegee Airmen program, which was also called the Tuskegee experiment at the time, when it finally has a possibility of happening, everyone is lobbying to be the place, including the Coffey school, and Tuskegee won, probably because they were willing to segregate.

So that was very heartbreaking for the, for our aviators, but it also, it advanced Blacks in aviation, Black people in aviation, but not in the leap that it would have been if it had ended up in Chicago instead.

[00:52:25] Elizabeth: Their president, Tuskegee’s president who wrote a big, long unpublished a diary really about the Tuskegee program actually says that in making their bid to the federal government to have the combat program rolled out at Tuskegee. They thought it might be comforting that it was in a segregated state. That was the word he used.

[00:53:02] Sherri: Yeah. Totally kowtowed to the prevailing fears of the white segregated military.

Yeah. And that was really heartbreaking for people who’d been fighting for equality. But at the same time, you can’t deny that it allowed the program to happen, and the program itself had all kinds of challenges, but Coffey School ended up training a lot of, they had their own CPTP program, and so they’re training people through that program to become instructors at the program so that they can go from basic to advanced training.

And then those people are getting hired away by Tuskegee, who needs them to teach the military people. One of the interesting things that is Janet Harmon Bragg. So when the war starts up and the war footing happens all of the sort of private schools the Coffey school shut down. It converted to be this CPTP program.

She started her own flight school for a while, but in order to get training, she actually ended up going down to Tuskegee. And getting some of her advanced training down there.

[00:54:11] Elizabeth: She’d maintained, through Johnny, she’d maintained a really good relationship with Tuskegee. She’d helped, they, when they won their bid for flight training, they did not have their own airfield.

And so they were doing fundraising all over the country for money to build an airfield for Tuskegee. And Janet had, both Janet and Johnny had been very much involved in this giving speeches around the country and helping to fundraise for it. So she had, she knew the people there. She had a good relationship with them.

And when she needed further training, it was the obvious place for her to go.

[00:54:47] Sherri:. And obviously there were only so many African American pilots of that caliber. So one guy, Charles Chief Anderson, they nicknamed him Chief. He was running the program down at Tuskegee and she had met him. He’d visited the Coffey school before.

And so she reached out to him and was like, I need this training. Can you help me? And he was like. Absolutely. Come on down. And really funny where Tuskegee where the airfield was in a dry county. And so she became a bootlegger for a little while. She would fly to the next county and they would load up her plane with booze.

And she had instructions from the soldiers. there. Yes. Yeah, she was. She had instructions from the soldiers. They had some sort of signal and she was supposed to dump it all into a lake. If the coast was not clear.

[00:55:41] Elizabeth: She had no idea how she was going to do that while she was flying the plane at the same time.

[00:55:44] Sherri: Fortunately, she never to.

[00:55:48] Liz: What else is there to the story that you want to share before I start digging in a couple of little sidebars that I remembered I’m hearing you talk about.

[00:55:55] Elizabeth: I was going to say, I feel like we should tie up, because here we are in the war and they’re doing all this teaching and training.

When Sherri and I were writing this, we imagined that originally when we planned out how we were going to tell this story, we imagined it as a flight. And so each chapter was going to be like groundwork. Takeoff, cruise, …

[00:56:28] Sherri: Turbulence. Turbulence was the War chapters…

[00:56:33] Elizabeth: But we found that when we got to when the war was over, really with the, with not even just with the war being over, but really with the end of the, what had been the civilian pilot training program became the war training service that ended before the end of the war.

And that was really the end of the sort of the momentum that they had in terms of this working together that they’d been doing for so many years. And although they all kept flying, they were not doing it together. And Willa, for example divorced Coffey. We’re not sure when. She went off and moved to another town where she became very involved in the church and married a minister there and she wasn’t flying.

She was involved in her church work. She got her license back when she was in her 60s. And she was inspired to do that because she’d read a book about the civilian pilot training service a historical book. So that was Willa off doing her own thing elsewhere. And Janet became involved in a different, she was no longer flying either.

[00:58:09] Sherri: Janet had a whole career, like Janet, cause she was still a nurse. She started running her own retirement homes and nursing homes. And she remarried and they had this business together, but because she had maintained this relationship with Johnny, she was a known name for Ethiopian students coming to the United States, and she ends up becoming like an honorary ‘Auntie’ to all of these Ethiopian students coming to, and she even gets to meet the emperor of Ethiopia, and then eventually is invited to Ethiopia to tour the place and visit all of her honorary nephews.

[00:58:53] Elizabeth: And Johnny had, he’d done this flying in Ethiopia in the 1930s. He actually, at the end of the war, went back to Ethiopia and he lived the rest of his life there. He was killed in a flying accident in 1954. But, he lived the last nine years of his life in Ethiopia doing various aviation related things out there.

So they all really, after the war ended, they went very different ways.

[00:59:26] Sherri: And Coffey, actually, he ended up teaching aviation in Chicago High School. He helped convince them to start a training program for young people. And so he taught for many years. And Coffey is funny. He was the oldest of them first born and lived the longest.

And he was flying into his 90s. And he taught until retirement age and then he was still, it’s funny, there’s like a whole file of receipts because he still trained people and would do their tests, run their tests. And he had all these receipts for like repairs and things that he meticulously kept in his later years.

And then there was a bit of a renaissance for them in the, starting in the 80s. Where people started remembering their legacy. And so the Smithsonian had a traveling exhibit called Black Wings, and they brought whoever they could find surviving aviators from that period to speak and do different events around the country. And so you’ll see Coffey and Janet in particular, those two popping up with several other people, Chief Anderson and the Smithsonian actually interviewed them on video, which is incredible to have. And let’s see. I’d say one of the last sort of crowning things for Coffey was Midway airport in south of Chicago named an approach after him.

So there’s the Coffey fix.

[01:01:08] Elizabeth: And now just last year, just in 2023, he was inducted into the is it the National Aviation Hall of Fame?

[01:01:16] Sherri:…the National Aviation Hall of Fame. Finally, after a really long career as a an aviator. He was acknowledged in that way. And then the other little tidbit that we add in the book is the next generation, right?

There was the sky and then there is outer space. And so the little connection to our people is that the town of Robbins, Illinois, where they built their first airstrip and had to bury the boulder, the mayor was a guy named Samuel Nichols. He had a daughter named Nichelle, who was,

[01:01:56] Liz: I just got goosebumps!

[01:01:58] Elizabeth: She was born. She was born the year that they were flying there.

[01:01:59] Liz: Oh, my Gosh!

[01:02:04] Sherri: So she goes on, she was a singer and dancer. She used to perform as a teenager in Chicago at cabarets and things. And she goes on to become an actress. And then we all know and adore her as Lieutenant Uhura from Star Trek. And in her later years, she became an ambassador for NASA and was helping them with recruitment and promoting things.

And she had stuck with Star Trek because she was going to quit after a couple of years in Star Trek and Martin Luther King met her at an event and told her he was a fan and that that the Black community needed her to stay on that show because it opened up such horizons for people.

And so she was paying that forward as an ambassador to NASA and she is the person who contacted a woman who had applied to be an astronaut and been rejected she reached out and said, would you please apply again? And that woman was Mae Jemison, who became our first Black female astronaut.

[01:03:07] Liz: That’s beautiful.

That is a beautiful circle right there. I love that story so much.

[01:03:14] Sherri: It really is about community. I think that’s the thing that strikes me the most about this book. It’s about what a community could do. So finding your community and all pulling in the same direction is incredibly powerful.

[01:03:25] Liz: Yeah, it is incredibly powerful.

However, there was like a little bit of a sad part of that. When you spoke, Sherri talked about your brother, you guys growing up in Chicago and being right there. Talk a little bit about that.

[01:03:42] Sherri: I was born in Chicago, moved away when I was a baby, but I was back there eighth grade through high school, and my brother was there for high school.

My brother was a kid who he built model rockets and model airplanes like his entire childhood. And he was a math science major in high school, and his aspiration, he did end up going to the University of Illinois in Champaign Urbana and majoring in aeronautical and astronautical engineering.

But I was stunned in researching this book to realize that Coffey and Janet and Willa, they were all in Chicago at the time that we were in Chicago in school. And we never heard about them, never heard about them. And also in doing the research, I discovered that another early Black aviator, William Powell, he was the first Black man to graduate from the engineering school.

Illinois and Champaign and my brother went there for four years and never heard of him. And so when I was working on the book, I asked him, I said, what would it have done for you to know about this legacy? He said, it would have changed everything. There are studies that show that students that are taught that there were trailblazers that looked like them that were from similar backgrounds, they do better in school, knowing that they are standing on those shoulders.

And so we do a huge disservice when we hide these accomplishments when we forget about this history. So I wish that I wish that he’d known back then, and I’m glad that he knows now. My dad also, he wanted to be a pilot but he, when he served in the military he wore glasses.

So he wasn’t allowed to learn to fly, but he did go for his private license in later years. And I just, I wonder, like the world would have been a different place, the world would have been a different place. My dad could have learned to fly with Cornelius Coffey.

[01:05:48] Liz: You’ve done so much for this history.

Why do you think we kind of lost track of it? Why do you think it gets buried in the crevices?

[01:06:00] Elizabeth: A part of it is because Coffey is a very unassuming guy. He maybe if Johnny had lived 50 years later, he’d have been blowing his own horn out there. But I, Bessie Coleman died in 1926.

I think he gets buried because. Things just drop away from us and there’s the, I run into stuff all the time that I thought was very important or incidents that were important in my childhood or in my teenage years. And nobody remembers them anymore. The younger generation has their own issues that are pressing.

That’s my guess is that these guys were quiet trailblazers. They did the work they had to do at okay, so they flew to Washington and it was all over the Black newspapers, but then a war happened and they were working to do what they needed to do to train pilots for that and they weren’t that the newspapers stories drop off.

After they start their successful school because every now and then it’s something like the school was closed for a week because they haven’t got the right runway light but they’re not. So much reporting about the achievements of the hundreds of students that they’re sending through and then sending on to train as military pilots.

[01:07:37] Sherri: I’ve got a different take on that. I think it is silencing by the majority. I know that when the Tuskegee Airmen, there was a propaganda film called Wings for This Man that was narrated by Ronald Reagan, actually. And it was one of those Black and white films showing Black pilots and saying look at what we’re doing.

Only shown in Black theaters and Black townships. So white America, which is the majority and still is. Didn’t know anything about it. In my research on the Tuskegee Airmen. I remember reading a story of a woman who mentioned in her history class in college, Oh, my dad was a pilot in World War II, this African American woman, and her teacher accused her of lying.There were no Black pilots.

I came across this with the women’s air force service pilots research I did for fly girl that my, I started that book as a Master’s thesis and my advisor when I told him what the book was about, he said, Sherri, I served in World War II. I’ve never heard of these women.

So when the WASP program closed, all those women were expected to go back to the kitchen, go back to being wives. And the handful of outspoken ones became bush pilots in Alaska. When you think about the end of World War I African Americans had served with distinction in Europe, the Harlem Hellfighters in World War I, and their reward coming back to the United States was, in 1919, was Red Summer.

They were killed, their houses were burned down because America was terrified by the image of a, an organized group of Black men that knew how to use guns. And so there’s no reward for success in the eyes of the majority. And so you keep quiet about things. There’s that. There’s a parable that I guess I probably shouldn’t say, but because there’s an explanation.

It’s the story of a bird is flying south for winter and it’s flying late and it’s freezing cold. It gets caught in the storm and it just freezes. It falls to the ground in a barnyard and it thinks it’s going to die. And a cow comes along and doesn’t notice the bird at all, but the cow takes a dump.

On the bird, and it melts the ice, warms the bird up, and the bird is so happy, it starts to sing, and the barnyard cat hears it, scoops it out of the manure, and eats it, and the the moral of that story is those who crap on you aren’t necessarily your enemies. Those who pull you out of crap aren’t necessarily your friends, and if you’re warm and happy in a pile of crap, keep your mouth shut.

And so I think there is something to be said there that progress was being made. Also, these are not the people that were women and minorities weren’t ending up in the history books back then. I know of WASP who started speaking about the history when they discovered that it wasn’t being taught in the history books.

And I think probably African Americans assumed it wasn’t going to be taught in the history books. So they weren’t keeping diaries. They were making their way through life. They were living. They weren’t building historical legacy because there’s a lot of erasure to that historical legacy.

So I think that’s part of it too, is that they did what they came to do. It might have lived on in smaller communities. And then it is time and tide, right? Somebody dies out.

[01:11:21] Elizabeth: Yeah, no, I think you’re right, Sherri. But I think it’s both. Yeah, it’s a combination. Unfortunately, it’s one of these things that if, it might not be as bad if it was just the one, but with both those things at work, it’s just going to get lost.

[01:11:38] Sherri: Yeah. Think of there’s so much that we’ve lost, but the plus side is that means we get to write another book, right?

[01:11:50] Elizabeth: Right?

[01:11:52] Liz: Keep Sherri and Elizabeth in business. Keep burying those fun and fascinating facts from history because they will go find them and bring them to light. And you both do that so well. What do you hope that this book accomplishes now that it’s published?

[01:12:05] Sherri: For me, I hope that I hope that it inspires people. I remember with Fly Girl I was doing a signing at the Air and Space Museum in D. C. and there was these two adult women pushing their mom towards me.

And I was like, what are you afraid of? Like kid lit authors don’t bite. And she they said she wanted to be a pilot and she she never achieved that dream. And we want to encourage her again. And I signed a copy of the book to encourage her. And it was just wonderful to see her light up.

And so I hope that this book lights some people up and that light guides them to go pursue whatever dream it is, whether it’s in aviation or astronautics or something completely different, just like yeah, just inspire them to do the thing.

[01:12:59] Elizabeth: Yeah, I can’t really add to that.

[01:13:01] Liz: I want to know a little bit about how you put this together, but before we go there, I just want to if, yeah, if anybody who is just interested in the aviation history and not how the story got written, then they can move along, but I just want to mention a couple of things.

First of all, had I been tracking this book, and it’s entirely my fault, when we were making our decisions about, books that we would do for the Aviatrix book club this year. I absolutely would have chosen it for this month for Black history month. but just in general to celebrate this history, this important history anytime of the year.

So I’m glad that I have the chance to talk to you. Everybody go buy the book because it is readable for everyone. It’s it’s shelved as a young adult book. And so every once in a while I’m reading it and I’m, I get reminded that you’re explaining something to me as if I might be a teenager and not have, but not have a whole career in it

[01:13:57] Elizabeth: and not be like, a retired Coast Guard pilot.

[01:13:58] Liz: I’m surprised when I get to that because I’m like, Oh yeah, I’m reading a young adult book.

This is a great read for any age. So informative. I also love the way that, like, I love being surprised by things that I learn about in history and reading books that feature, I say this all the time, that reading books that feature women in aviation open a portal for me in ways that I might not go dig down that history myself.

And I just want to say this, Elizabeth, about both this book and I am still enjoying the audio book, Black Dove, White Raven, and this history of Ethiopia was just so surprising. I’ve studied like different parts of Africa for a variety of more national security and post-colonial crises and stuff like that, and just never got into the history in Ethiopia and the connection of the Blacks in the United States.

That history. So thank you for the way that you do that for us. And I just want to say that the Aviators Book Club is discussing Stateless this month, which is also by Elizabeth Wein and so much fun. It’s such a great read. And I look forward to hopefully seeing you in the discussion at the end of the month on Sunday.

[01:15:08] Elizabeth: I got Sherri to blurb Stateless…

[01:15:12] Liz: You have a little love fest is going on…

[01:15:15] Sherri: That’s a great book.

[01:15:16] Liz: And then you had to go get, who was it, Jacqueline Brown to blurb this one?

[01:15:21] Sherri: Jacque Woodson, yeah. Jacqueline Woodson. Yes,

[01:15:24] Liz: Jacqueline Woodson. To blurb yours, which is pretty special. Pretty special. And a whole bunch of other really great people on the back of this book.

[01:15:32] Sherri: Yeah, I was astonished at like how many people were willing to step up and blurb this book. Really grateful.

[01:15:40] Liz: Of course. Yeah.

So, you shared that you guys actually had not physically met in person until you started actually writing this book.

Talk about that a little bit.

[01:15:52] Elizabeth: We’d met on Zoom. We had written some preliminary material for the book. And we needed to up our game and we planned to have a working week together in the fall of 2022. And so we did. We met in the middle. Sherri lives in California. I live in Scotland. We met up in Pennsylvania at my family home.

And we spent a week there. Pulling together everything that we’d done. And this sort of, the story is that we both, because we’ve been working on this thing for three years already by the time we actually met. From the time that we started pitching it to the time that we met was about three years, the pandemic was in there it wasn’t meant to be that long, but we both were kinda like, Oh, geez, she must think I was such a waster.

We both had this impression that we weren’t getting anything done. And that when we presented whatever it was we had done to the other person, they must surely be looking at it going, really? And what was so nice about getting together was that we realized that we were both being very cautious about the other person and worrying too much and that we were actually on a level where we both were procrastinating equally…

[01:17:29] Sherri: But also being productive equally…

[01:17:35] Elizabeth: Yeah, but also being equally productive in different ways, I hasten to add. One of the things that getting together really, I think highlighted for us was how differently we work because Sherri is a plotter and I am a pantser. Sherri had all these very careful outlines and very detailed outlines timeline and it was, she was the one who came up with the, with all the different chapter titles and did the, we had to do a lot of outlining before we were able to actually pitch this book. And I, meanwhile, I’m like, okay, I’m just going to write this. I got all this pile of research here and I’m just going to write it all down. And maybe I’ll get somewhere at the end.

[01:18:25] Sherri: I just don’t know how you do that because you’re so meticulous, too. It’s one thing if you’re doing it broadly. Because I make all

[01:18:33] Elizabeth: Because I make all these little notes to myself. I make all the notes are all in there. And if I didn’t do that, I would have no idea.

[01:18:38] Sherri: Yeah. Whereas I, like I, I described it as a murder wall. I had like sheets of paper, like I had a full outline and I was trying to do a timeline. Cause that’s the thing that’s always kicked me in the teeth in revision in historical fiction is that you then realize that your timeline is wonky somewhere and the story that you think is working so beautifully actually doesn’t work. So getting the chronology right and then trying to move those pieces every time you got more information and this Elizabeth was great at is that you’d have to judge where you thought this happened when Elizabeth would be like over here, it says this date, here it says this date.

So we would triangulate. And so I had this thing that I taped it on my wall so I could visually see it. My husba,nd walked into my office and was like, what are you doing? And I’m like, I’m following timelines and seeing the future, it was a crazy making thing.

So when you’re writing it can be messy, right? It’s like trying to make Thanksgiving dinner. And, tell everybody, stay out of the kitchen. I don’t want you to see what this is going to look like until it’s done. But then when you’re writing with a partner, you’re like, okay, you get to see how the sausage is made.

And that’s embarrassing like you don’t want anybody to see it. So that was very intimidating. But then, so that was like the beauty of being together in Pennsylvania is we’d sort of, you know we got to see each other in our pajamas, and be human beings, and know that we’re both working really hard towards the same goal.

And blessing of blessings that we actually like each other and we get along.

[01:20:22] Liz: I was going to say, for you guys to go through that. I guess we got lucky. To have a work relationship like that when you hadn’t had any kind of relationship before and to get through the whole thing and come out on the other end appearing at least to the public that you still like each other. Congratulations. That’s awesome.

[01:20:39] Elizabeth: Thank you. I think if we had really not rubbed that, like if we’d really rubbed each other the wrong way if we hadn’t gotten along, I think we probably could have written a book together. I think we’re professional enough that we could have gone, Oh, God. Okay.

I’m just going to do that. I think it could have happened. It probably wouldn’t have been as good. And we probably wouldn’t have been able to go and talk to those schools together.

[01:21:12] Sherri: It would not have been as fun. I think that’s the thing is, yeah, it wouldn’t be fun. And it’s, it is like a gift of the, from the book and it’s a bonus, but cause I actually would hesitate to write with somebody that I was friends with.

Because then I don’t know that I could be honest about what I think is working and not working on the page. In fact, I’ve avoided working with other people because I’m like, oh, I don’t want to go through that. Yeah, it doesn’t always work, but this worked really well.

[01:21:43] Liz: So you guys, like, where, at what point was this being pitched?

To, and to whom? You, I know, Elizabeth, have an agent, Sherri? How does that work? How do you navigate that? And when does it start going out to hopefully find a publisher?

[01:22:01] Elizabeth: Our agents worked together. We pitched the book to my nonfiction editor and to Sherri’s editor. And ..

[01:22:14] Sherri: Let them duke it out.

[01:22:15] Elizabeth: Got it better. We let them duke it out, which they did and I like it. Sherri’s editor won.

[01:22:21] Sherri: But the way it worked Elizabeth had sent me a little write up of what the book would be. And then we decided to, I really enjoy writing pitches.Yeah, we talked about it, and then I made it sexy, right? And then we gave it some structure

[01:22:35] Elizabeth: You did, actually, you did a really good job. She’s good at this kind of stuff.

[01:22:40] Sherri: I like doing that. I like doing that. And then that’s what we went out with.

[01:22:58] Elizabeth: And, and we gave it, we handed it to the agents who were working together.

[01:23:01] Sherri: And they gave us feedback. I think they liked it. I think they liked it from the start and then they, and then we went back and forth and then yeah, and we got offers in and we chose one and then we were off and running.

[01:23:17] Elizabeth: But, as I recall.The contract was a little different from a contract that either one of us would have because it talked about how the fees were going to be split. But apart from that, it was pretty straightforward.

[01:23:36] Liz: See, so this is the thing that I I’ve said it a few times, but I just can’t emphasize enough. I have different, obviously, I since I’m dealing with books that feature women in aviation primarily They run the gamut of authors and genres. And so I get, so in my, and then you guys are like my Venn diagram overlap, right? Because I’m I have my Master of Fine Arts in writing for children and young adults.

And you guys are like icons in that community. And then I have my aviation community where obviously we have our own icons who, some of whom I’ve had the pleasure of interviewing. So this is the thing to emphasize to our pilot friends who maybe don’t know who you are is that this is like having two of the best known people in writing for children and young adults and you bring your credibility in the kid lit world as well as the canon that you’ve each built up of this having written in aviation before and Obviously have found an audience for it. And so for you to take that to an editor and them to snatch it up that’s just a huge favor to our community for the visibility of Black history and aviation, because many people could have written the story it may not have gotten where it can get because you two wrote it together.

[01:25:02] Elizabeth: I think that part of the success that we have had in terms of pitching and publishing this story and writing it is the fact that we both have built a career already in writing, so we know who to go to. We have people behind us.

We know what we have to do in order to it’s not, it’s it, the whole publication process is not a mystery, although it can be a conundrum. We know what the process is going to be. There are sticking points throughout the process. And we did run into those, and we still run into that, but because we have been so long, both of us involved in publishing, I think it feels less mysterious to us than maybe if you’re breaking into it.

[01:26:07] Sherri: I also think that. Like we, because we’ve been writing for so long and what we write that we’re the comps for our own book here like when they’re like what would this be? Like, it’s okay, let’s look at Code Name Verity. So we could have blurbed this book ourselves in a way and I think that made it…

[01:26:31] Elizabeth: and we would have, if we weren’t both working on it.

[01:26:34] Sherri: And so that made it easier. That made it an easier sell. But if you’re breaking into writing, I think that the takeaways are, the advice I would give for somebody breaking into writing who wants to do a nonfiction like this, would be, yes, definitely work with an agent so you’ve got to convince an agent first, and then they’re going to help you get the best deal that you can get with a publisher.

They’ll get you to the more traditional publishers. Photo permissions are a huge challenge. Get somebody else to do that. So find somebody who is, who knows how to do that, to help you do that, and start early. And annotations. The last 80 pages of this book are all annotations for our sources, and that is all courtesy of Elizabeth’s beautiful mind.

I’d say, take meticulous notes and keep track of that. And then give yourself the time to include it. Also, for nonfiction, quite often you are doing a book proposal, rather than handing over an entire written book. Yeah, I’m trying to do a book proposal right now, and I’m struggling with it, like a nonfiction adult book proposal.

I think it can be very challenging, so it’s possible for kid lit, especially if you have a track record, that you could just do a sexy pitch like we did.

[01:28:00] Elizabeth: I would add to that a couple of sticking points that I’ve found in pitching nonfiction are, I’ve had people that I find fascinating personalities turned down because they’re not kids. We are both. Writing YA and that’s what our publishers are looking for, stuff that is going to be of interest to young adults, and the other sticking point that we found in with this book, as I recall, was, Is it going to be exciting enough to be of interest to teens? And we really did.I don’t remember, this might have been, this might have been after, oh my gosh, we had this call where, nevermind. It was Sherri had to leave in the middle of the, Sherri had to leave in the middle of the call, and I think that it was when I was finishing that this question came up, and it was, is there enough exciting material in this book to make it interesting to teen readers?

And I was like yeah Johnny’s going to get chased by fighter pilots in Ethiopia and the wind’s going to blow down their hangar. And I was like, yeah, of course it’s going to be exciting. But. I found myself having to play those things up and I actually don’t feel that we should have to play those things up that people will find things interesting, even if they don’t find them exciting, but.

In making a pitch. It’s just something to bear in mind.

[01:29:49] Sherri: Sexy. It’s the thing, the thing I learned about pitching because I used to work at Disney and a lot of my work was, I was a development executive and we were pitching ideas all the time. And you sell the sizzle, not the steak. So what’s gonna make people walk into the room and go, oh my gosh, that smells so good, I cannot wait to eat it.

Because the minute you give them the steak, they nitpick. They go, Oh, this is overcooked. This is undercooked. But if they just smell that fat and the umami they’re like, Oh, and then they’re imagining what it’s going to be. So that would be my advice there is yeah, if you get too into the weeds, and that’s, what’s challenging about writing like a full nonfiction proposal is you’re in the weeds.