Women in Aviation History: Pancho Barnes

Raising Hell: On the Life and Times of Pancho Barnes

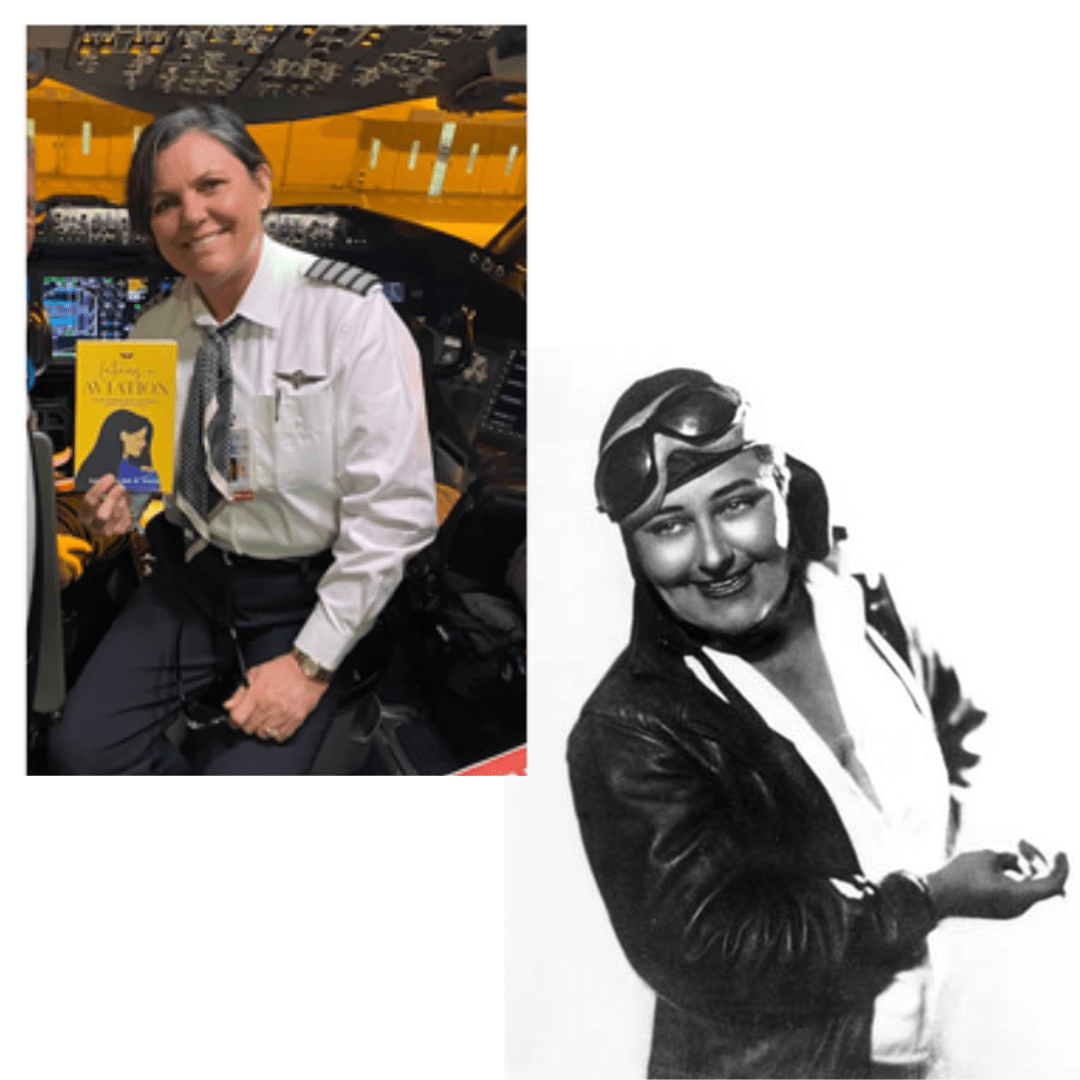

by Linda Pauwels

During the 1920s and 1930s, the ‘Golden Age of Flight’, the free-spirited Pancho Barnes blazed trails as a barnstormer, a racer, a cross-country pilot, and a Hollywood stunt pilot. She flew faster than Amelia Earhart, was a favorite of the Hollywood set, and later in life, ran the wildly successful desert watering hole known as the Happy Bottom Riding Club, portrayed in The Right Stuff.

Pancho lived a full, messy, and oftentimes literally dirty life. She defied all convention, spending three fortunes, running through four husbands, and enjoying the company of countless lovers. Pancho did not like to bathe, had a legendary foul mouth, and easily outdrank the best of men. According to one contemporary, “she did not have one single inhibition.” Pancho flew “to keep from exploding” and because flying “acts as a safety valve so far as I am concerned.” She left an indelible mark in early American aviation history and helped redefine the role women would play within it.

The Early Years

Pancho was born Florence Leontine Lowe to a wealthy Pasadena family on July 22, 1901. She grew up on Millionaire’s Row in San Marino, in a thirty-five room mansion, with an array of servants who catered to her every need. Unlike her older brother, William, a frail boy with fine features, Florence was sturdy and energetic. Alas, she was not endowed with the delicate features desired for a girl. Instead, Florence inherited narrow hips, muscular legs, broad shoulders, a short, thick neck, and a round, moonlike face. Pretty, she was not. Indeed, Chuck Yeager, a good friend of Pancho’s later in life, thought she was the “ugliest woman he had ever seen.” But there was something about her that appealed to legions of stubborn, opinionated, strong-willed aviators. Intuitively, they knew she was one of them- a kindred spirit.

From her paternal grandfather, Thaddeus Sobieski Constantine Lowe, Florence got her overabundance of confidence and love of adventure. Grandfather Lowe was a pioneering balloonist, engaged by the Secretary of War to start the Army of the Potomac’s first military balloon corps during the Civil War. Lowe was also an inventor who held several patents. At one time, he was one of the richest men in America. By the end of his life, however, Lowe had none of his fortune left. In more ways than one, his granddaughter would follow in his footsteps.

Florence was brash. She was strong. She had spunk. And from the beginning, her father and grandfather genuinely loved her for it. They raised her like a boy, freely passing on their enthusiasm for the outdoors, hunting, and horsemanship. The veteran aeronaut even took his young granddaughter to see her first air show at the age of nine. “Everyone will be flying airplanes when you grow up,” he told her. “You’ll be a flier, too.” And it came to pass that airplanes ranked with men, horses, and dogs as Florence’s greatest passions.

Florence’s mother, however, did not know how to handle this overexuberance of spirit, which she felt was unseemly for a female child. So, the increasingly headstrong, rebellious girl was shipped off to a series of strict private academies, boarding schools, and convents. When it became apparent she could not be reformed, Florence was married off, at age 19, to C. Rankin Barnes, the handsome rector of South Pasadena’s Episcopal Church. At the time, Florence had never even kissed a man.

When the marriage was consummated, after four days, Barnes told Florence “I do not like sex. It makes me nervous. I see nothing to it, and I do not wish to have any more of it.” A son, William “Billy’ Emmert Barnes, was born exactly nine months and one day after Florence’s only intimate encounter with her husband. She remained Barnes’ wife, in name only, until 1941, and would later marry three more times.

How Pancho got her Nickname

Florence’s mother died unexpectedly in 1923, when Florence was 22, leaving her a significant estate. Flush with cash, Florence, who had no maternal instincts to speak of, left Billy in the care of nurses at the Barnes’ home to pursue her varied interests and explore newfound carnal appetites. She built a home in Laguna Beach, rode horses, entertained, and traveled extensively. One night in 1927, during an alcohol-fueled party at her Laguna Beach home, Florence and a group of male friends decided to hire on as crew aboard a Mexico-bound cargo ship. She disguised herself as a man and the group boarded the Carmina at San Pedro Harbor, bound for San Blas, one of the wildest seaports on the Pacific.

Unbeknownst to the group, the Carmina was running guns to Mexican revolutionaries. She and friend Roger Chute were lucky to escape with their lives. It was at the beginning of their seven-month “hobo trek” though Mexico that Florence, teasing Roger aboard his white horse, shouted from atop her burro: “If you don’t look just like a modern-day Don Quixote riding such a skate.”

Roger laughed: “In that case, you must be his companion, Pancho.”

“You mean Sancho,” she corrected him. “Sancho Panza.”

“Ah, what the hell, Pancho or Sancho, you fit the bill. From now on, I’m calling you Pancho,” Roger concluded. Florence was delighted with her nickname and kept it for the rest of her life.

Into the Air

When Pancho returned from her great Mexican adventure, the country was abuzz with the triumph of Charles Lindbergh’s flight to Paris. In 1928, Pancho found an instructor who reluctantly agreed to teach a woman, bought a Travel Air biplane for $5,500, five times what an average family earned in a year, and managed to solo in six hours. She celebrated her solo by taking a friend up and buzzing the field while he wing-walked among the flying wires. From that point on, aviation dominated Pancho’s life. “Aviation is my real calling… I think I will stick pretty close to the airplanes,” she wrote to Barnes.

Pancho took great pride in becoming a skilled pilot as well as a practical mechanic. Then, along with a handsome parachute jumper named Slim, she went on barnstorming tours with her own “Pancho Barnes’ Mystery Circus of the Air.” In August 1929, just one year after her solo, she joined nineteen other women in the first Women’s Air Derby, the precursor to the “Powder Puff Derby” air race flown until 1977.

The following year, Pancho purchased a powerful Travel Air Model R Mystery Ship for a whopping $12,500, plus $650 for additional equipment. On August 4, 1930, Pancho Barnes became the fastest woman on earth, clocking 196.19 miles per hour to beat Amelia Earhart’s women’s world speed record.

In hopes of adding to her flying opportunities, Pancho honed her acrobatic skills and used well-established connections to become one of Hollywood’s favorite stunt pilots. She formed a company, hired three other pilots, and encouraged studios to contract with her. Among several films, Pancho worked on Howard Hughes’ blockbuster, Hells Angels.

The Happy Bottom Riding Club

As the nation sank deeper into the Great Depression, Pancho’s aviation gigs dried up. A total lack of interest in money management and utter disregard for the consequences of unbridled spending left Pancho with only one property, which she traded in 1935 for a small, quarter section ranch in the western Mojave Desert. There, on the “ass end of the moon,” she settled with her twelve-year-old son, Billy, and a foreman and crew. One of the first things she did was scratch out an airstrip on the desert bed so her friends could fly in to visit. Pancho grew alfalfa and raised livestock: dairy cows, hogs, and horses.

Just two years earlier, in 1933, the Army Air Corps had settled into the same area, setting up a bombing and gunnery range to serve the fighters and bombers coming out of March Field. Pancho’s ranch provided pork and milk to supplement Army rations. Business was good and she expanded the ranch from 80 to 368 acres. She also enlarged the home and built a swimming pool. Then, as war became imminent, the Army expanded its operations as well. The gunnery range became the Muroc Air Field and permanent runways were built. Almost overnight, a large military installation sprang up, with officers and enlisted men reporting in large numbers.

Pancho displayed a keen patriotic spirit and was delighted by the turn of events. She happily made her ranch and its growing amenities available to off duty fliers. Pilots used her swimming pool, rode her horses, ate her steaks, and partook in libation-induced hangar talk until the wee hours. The airmen loved Pancho’s hospitality, the food, the liquor, and the pretty hostesses she had hired to entertain them. The men were soon joined by high-ranking officers, like James “Jimmy” Doolittle, a friend of Pancho’s from her racing days, who was now sporting three stars. The commander of the Army Air Corps, General Henry “Hap” Arnold, was another frequent guest at what became affectionately known as the Happy Bottom Riding Club.

After WWII, Muroc Air Field became Edwards Air Force Base, the nation’s leading experimental flight testing center. Test pilots replaced the wartime fliers. In this area of limited resources, Pancho’s place remained wildly popular with off duty pilots, who needed a congenial place to relax and let off some steam. One of Pancho’s favorites was Captain Chuck Yeager. The sonic-busting test pilot and the high-flying hostess formed a strong bond which became a lifelong friendship.

The End of an Era

In 1952, a new commander arrived at Edwards Air Force Base, and the entire atmosphere began to change. In The Happy Bottom Riding Club, biographer Lauren Kessler explained how “by the early 1950s, the brash camaraderie of the war years was giving way to the spit and polish of the modern military.” The cocky, risk-taking test pilots were replaced by conservative managers of technology who followed the rules.

Edwards AFB continued to grow, becoming almost unrecognizable. The base used eminent domain to acquire adjacent land and one by one, Pancho’s neighbors sold to the government. However, she was emotionally attached to her land and refused to sell for a “pittance.” Pancho took matters into her own hands and filed several suits against the U.S. government, taking charge of her own litigation. In November 1953, a suspicious fire burned down Pancho’s property. She had to move out, but continued the legal battle. In November 1956, a jury rendered a verdict in her favor. Pancho had beaten the government on her own terms, and was awarded more than twice what the government had originally offered for the land.

Sadly, money meant nothing to Pancho. It was only a means to an end, and she would have given it all away to have her land back. She never fully recovered from the considerable psychological blows received during the battle of the Mojave. After leaving the ranch, Pancho endured some very difficult years. Her health declined and her effervescence slowly extinguished. She died in 1975, alone in a shack, with only her dogs for company. Until the very end, Pancho was a woman who lived as if life had no consequences. Perhaps one of the best ways to summarize her life is to use her own words about the times she shared with fellow aviators at the ranch: “We had more fun in a week than most of the weenies in the world have in a lifetime.”

References:

Kessler, Lauren. (2000). The Happy Bottom Riding Club: The Life and Times of Pancho Barnes. New York: Random House.

Spark, Nick T. (2006, July/August). A Woman Called “Pancho”: Remembering Florence “Pancho” Barnes. Aviation for Women.

Florence “Pancho” Barnes- Aviation’s Companion. Air Racing History, www.air-racing-history.com/pilots.htm

Photos courtesy of Pancho Barnes Trust Estate.

Paper originally submitted March 3, 2010, for DAV 711 – Foundations of Aviation, Embry Riddle Aeronautical University, Dr. Tim Brady, Ph.D.

Captain Linda Pauwels is a B787 Check Airman for American Airlines, and the curator of the pilot poetry collection, Beyond Haiku. In the mid-2000s, Linda wrote a regular column, titled From the Cockpit, for the Orange County Register. She has been secretly writing poetry for a while. Unfortunately, that cat is now out of the bag.