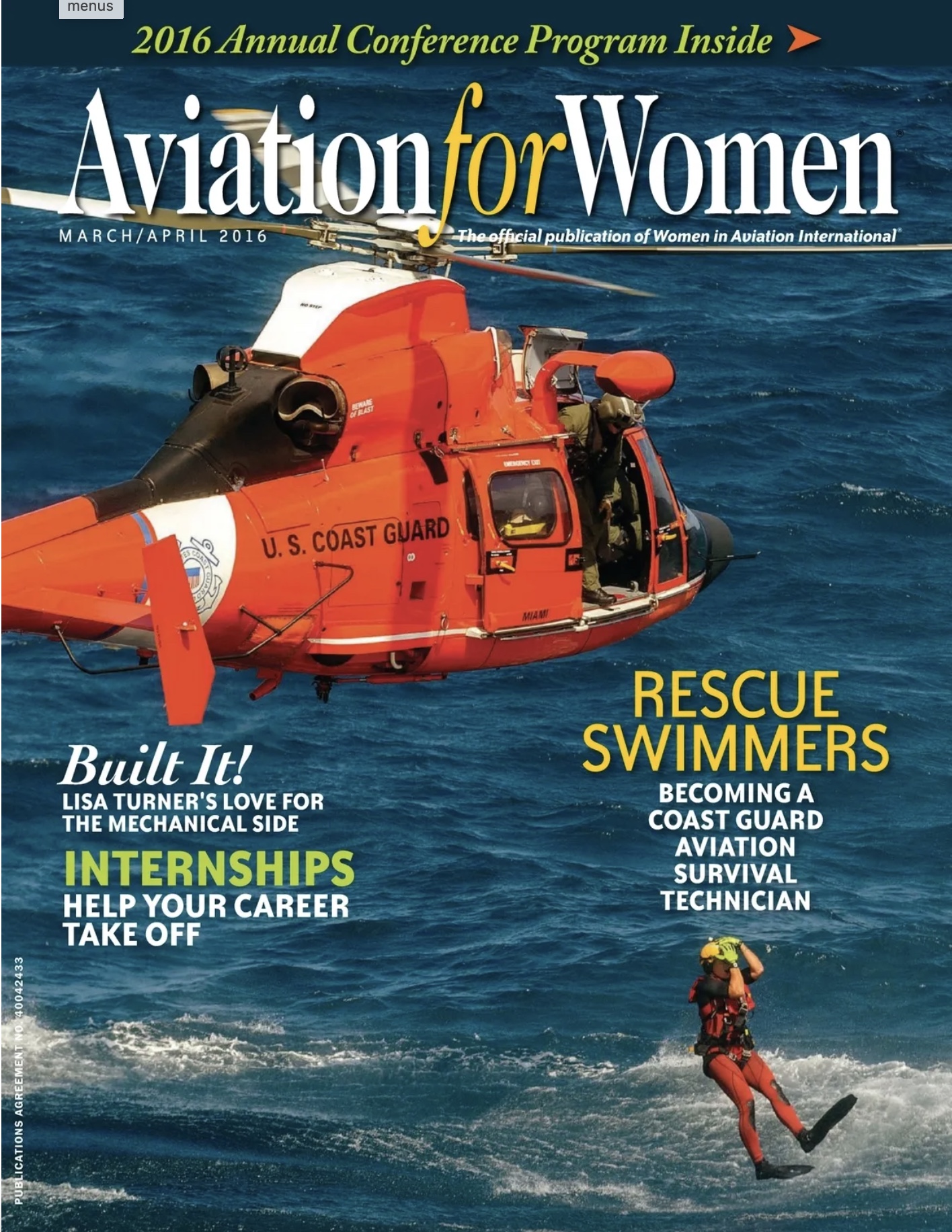

U.S. Coast Guard Rescue Swimmers (AFW Apr/May 2016)

by Liz Booker

posted Jan 2021

I recently watched the movie, The Guardian, for the umpteenth time, and found myself getting emotional in ways I never did when I was on active duty. I think when we’re doing a job, we do our best to block out our emotions about it, especially when it’s something potentially dangerous or life-threatening (at least I apparently did). I mean, I was proud and pumped up by watching it, don’t get me wrong, but watching it now, with a little distance from my active Coast Guard flying career, I saw the deep humanity in it—these brave souls who jump into the water to help someone who is completely at the whim of the elements or their injuries without them.

When I enlisted, I saw the picture of the guy in the orange suit, mask, and fins, dangling from the cable of a helicopter on my recruiter’s wall. I pointed to the picture and said, “I want to do that.” I’d always wanted to be a pilot, but that wasn’t an option for an enlisted member. I figured whatever that was would be the next best thing.

“Sure,” said the recruiter. “Sign here.”

In boot camp, I was the first person in my company to slap the wall outside my Company Commander’s office and recite all of the required knowledge to lose the ‘green belt’ we were required to wear until we did so. When he asked what I wanted to do in the Coast Guard, I told him. “I want to be a Rescue Swimmer, Chief!” This unleashed a tornado of senior enlisted members screaming at me in front-leaning-rest (push-up position) for what felt like hours (it was probably fifteen minutes). “Down, up,” they repeated over and over. It felt like hazing, for sure, but these men were teaching me a lesson. If I really wanted to be an Aviation Survival Technician (AST), I’d have to endure intense physical discomfort for long periods of time; I’d have to build my upper body strength to special forces requirements; and, while not obvious in this lesson, but crystal clear to me as I learned more about their role, I’d have to face my biggest fear–the deep, dark, terrifying open ocean.

Well, I chose another path, and ultimately ended up at the controls of one of those helicopters, with those brave souls not only at the mercy of the scary abyss, but also at mine.

I rolled into the gym the morning after watching The Guardian excited to see my AST friend who still stands the watch at Air Station Miami. Like one of the characters in the movie, my friend is a ‘re-tread’, as are many other AST’s who go to training and get washed out, but go back and ultimately succeed. I compared notes with him. “How accurate was the training?” I asked. He confirmed, it was spot-on, with the exception of the hypothermia scene. I already knew how accurate the procedures and conditions were. Pretty close. I think it’s a fantastic movie—the Coast Guard’s ‘Top Gun’. I told my friend he should wait to see it when he retires, and feel the emotional impact it has then. He laughed and told me it was actually the reason he’d joined the Coast Guard. He was living in Alaska when the movie came out in 2006, and he called the recruiter the next day.

Even though I never became an AST, I’ve always been proud of the Coast Guard that ALL specialties have been open to women since well before I joined the service in 1991, including this most physically demanding rate. They just have to meet the same physical requirements. In 2016 I wrote the below article about the women who are still on active duty for Aviation for Women Magazine’s April/May edition. Chief Voorhees is now SENIOR Chief Voorhees, and she’s still in Atlantic City, N.J. ASTC Jodi Williams and AST1 Jaime Vanacore, are assigned to the AST training school in Elizabeth City, N.C., where much of the movie The Guardian is set. All three of these women are nearing retirement, and Jaime was the last woman to successfully complete the training. Who will be next?

This article was published in the April/May 2016 issue of Aviation for Women Magazine.

“What are your numbers?”

This is the first question Aviation Survival Technician Chief (ASTC) Karen Voorhees asks when any Coast Guard recruit expresses interest in becoming an AST. The ‘numbers’ Karen refers to in her question are, “How many pushups, pullups, and chin-ups can you do?” ASTs maintain the Coast Guard Aviation community’s survival equipment and provide high quality survival training to aircrews. They also train as Rescue Swimmers, a qualification that allows them to jump, and be hoisted, from helicopters into the water to assist maritime search and rescue victims, to rescue victims stranded on cliffs or ice, and to perform Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) services.

While the national debate continues about women’s physical abilities to train and serve alongside their male counterparts, the Coast Guard’s most physically demanding specialty has been open to women since its inception in 1985. AST “A” school is a grueling 24-week program based in Elizabeth City, N.C. and has a 74% attrition rate. This is with a pre-qualification physical screening that requires applicants to perform: 40 pushups in 2 minutes; 50 sit-ups in 2 minutes; 3 pull-ups; 3 chin-ups; 1.5 mile run in 12 minutes; 450 meter swim in 12 minutes; and four 25-meter underwater laps. The entire workout must be completed in under an hour, and standards for men and women are identical.

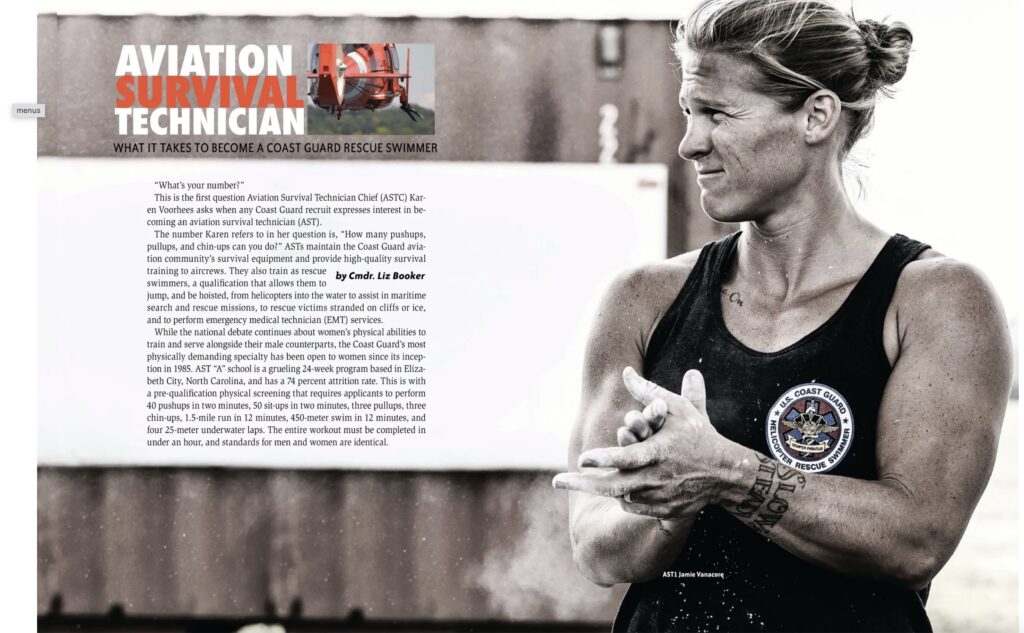

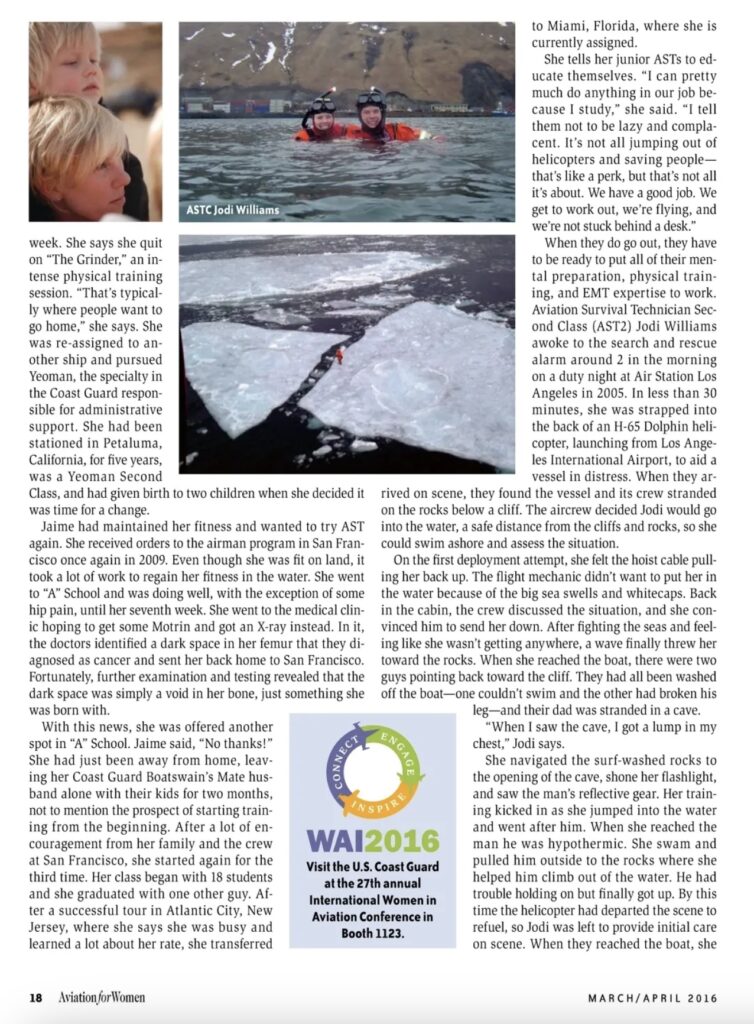

The first female Rescue Swimmer was Kelly Mogk, who graduated from training in 1986. Since then, six women have completed Rescue Swimmer and AST “A” school. Today, of the approximately 350 active duty ASTs, three are women—ASTC Karen Voorhees, AST1 Jamie Vanacore, and ASTC Jodi Williams—who traveled vastly different paths to succeed in a male-dominated specialty, but they all share hard-core physical and mental determination, and a passion for their profession.

In 1997, Karen was a 27-year-old cabana pool manager and wife of an ex-para-rescue jumper in Hawaii when she saw a Rescue Swimmer jumping out of a Coast Guard helicopter. She had recently read Dr. Laura Schlessinger’s Ten Stupid Things Women Do To Mess Up Their Lives, one of which, according to Karen was, “following their husbands around just floating through life.” When she saw that Coast Guard swimmer, something spoke to her.

Karen’s road to AST “A” school was neither short nor easy. Originally from New Zealand, she worked through citizenship and security clearance issues, then spent two years as a boat crew member at a small boat station in Oak Island, N.C. When it was her turn for AST “A” School, she was disheartened by resistance from the Warrant Officer responsible for issuing orders. Fortunately, her station Senior Chief, who had witnessed her work ethic, determination, and physical ability, intervened.

From the small boat station, Karen reported for the Airman program at Air Station Los Angeles. The Airman program was designed to allow AST candidates to prepare physically under the tutelage of operational ASTs for the demands of “A” school. Not everyone in the shop was supportive, even 14 years after Kelly Mogk’s success. For every guy who said she couldn’t do it, however, there were two who said she could, and were pulling for her.

Karen had a strong physical fitness foundation, but she still needed a lot of work. She was a competitive swimmer and skier as a child, but drifted away from exercise as a teen. At 20, she became a self-proclaimed, “born-again fitness fanatic;” she lost weight, did Jane Fonda workouts, ran, and instructed step-aerobics. Despite her preparation, she struggled with the pull-up requirement. She had three months to train, worked hard on pyramid pull-ups, and ultimately blasted the test.

The screening test just got her in the door. Once in “A” school, the challenges mounted. There, trainees are never well-rested when they complete the physical fitness test; it’s always after some other grueling workout. She overcame each new obstacle, but every day was a struggle for her—throwing up in the locker room, telling herself to get through this one day. She was seconds from raising her hand to quit after a hard workout when she had her epiphany. She looked down the line on the edge of the pool at her classmates, and saw them, snorkels drooping, tired—“defeated mouse syndrome,” she calls it—and realized that everyone else looked exactly the way she felt.

Karen advanced to AST2 in a year, and has since served at Air Stations Atlantic City, N.J. and Miami, Fl. In 2013 she became the first female AST to advance to Chief in Coast Guard history. Now she is back in Atlantic City as the AST Shop Chief with 15 ASTs in her charge.

Karen expresses concern about our culture when asked why there aren’t more women ASTs: “We pat our kids on the head and tell them they can be anything they want to be when they grow up, but we don’t tell them they have to work to get it. Men aren’t passing the PT test either.”

Master Chief Petty Officer Clay Hill is the AST Rating Force Manager at Coast Guard Headquarters in Washington D.C. He says the biggest obstacles to success in AST “A” school are upper body strength and confidence in the water. His advice to anyone hoping to succeed is to be able to do the physical test as part of a regular workout routine, not as the workout, and to be really at ease in the water. He says the most successful ASTs are those who, “play water polo, surfers, people who get in the water and do more than just competitive swimming; people who know the power of the ocean, who know what it feels like to get pulled down, held down, beat down in the water, and who do not hit the panic button.”

Aviation Survival Technician First Class (AST1) Jaime Vanacore echoes Master Chief’s assertion about water confidence. “You have to be calm when you’re being dragged underwater. It’s a different crossbreed. You have to be strong on land and in water, and you have to endure pain and discomfort. You’re going to be cold, you have to train to be able to drag a person through the water.”

Jaime first heard of ASTs in high school. She enlisted in the Coast Guard and served on a ship for a year before being assigned to the Airman program in San Francisco in 2004. She had played team sports—volleyball, softball, soccer—and grew up swimming in the ocean, but still had to work on her upper body strength.

At nineteen she went to “A” school, and quit during her second week on ‘the grinder,’ an intense physical training session. “That’s typically where people want to go home,” she says. She was re-assigned to another ship and pursued Yeoman, the specialty in the Coast Guard responsible for administrative support. She had been stationed in Petaluma, Calif. for five years, was a Yeoman Second Class, and had given birth to two children, when she decided it was time for a change.

Jaime had maintained her fitness and wanted to try AST again. She received orders to the Airman program, in San Francisco once again, in 2009. Even though she was fit on land, it took a lot of work to regain her fitness in the water. She went to “A” school and was doing well, with the exception of some hip pain, until her seventh week. She went to the medical clinic to get some Motrin and got an X-ray instead. In it, the doctors identified a dark space in her femur that they diagnosed as cancer and sent her back home to San Francisco. Fortunately, further examination and testing revealed that the dark space was simply a void in her bone; just something she was born with.

With this news, she was offered another spot in “A” school. Jaime said, “No thanks!” She had just been away from home, leaving her Coast Guard Boatswain’s Mate husband alone with their kids for two months, not to mention the prospect of starting training from the beginning. After a lot of encouragement from her family and the crew at San Francisco, she started again for the third time. Her class began with 18 students and she graduated with one other guy. After a successful tour in Atlantic City, N.J., where she says she was busy and learned a lot about her rate, she transferred to Miami, Fl., where she is currently assigned.

She tells her junior ASTs to educate themselves. “I can pretty much do anything in our job because I study. I tell them not to be lazy and complacent. It’s not all jumping out of helicopters and saving people—that’s like a perk—but that’s not all it’s about. We have a good job. We get to work out, we’re flying, and we’re not stuck behind a desk.”

When they do go out, they have to be ready to put all of their mental preparation, physical training, and EMT expertise to work. Aviation Survival Technician Second Class (AST2) Jodi Williams awoke to the search and rescue alarm around two in the morning on a duty night at Air Station Los Angeles in 2005. In less than 30 minutes, she was strapped into the back of an H-65 Dolphin helicopter, launching from Los Angeles International Airport, to aid a vessel in distress. When they arrived on scene, they found the vessel and its crew stranded on the rocks below a cliff. The aircrew decided Jodi would go into the water, a safe distance from the cliffs and rocks, so she could swim ashore and assess the situation.

On the first deployment attempt, she felt the hoist cable pulling her back up. The Flight Mechanic didn’t want to put her in the water because of the big sea swells and white caps. Back in the cabin, the crew discussed the situation, and she convinced him to send her down. After fighting the seas and feeling like she wasn’t getting anywhere, a wave finally threw her toward the rocks. When she reached the boat, there were two guys pointing back toward the cliff. They had all been washed off the boat—one couldn’t swim and the other had broken his leg—and their dad was stranded in a cave.

“When I saw the cave, I got a lump in my chest,” Jodi says.

She navigated the surf-washed rocks to the opening of the cave, shone her flashlight and saw the man’s reflective gear. Her training kicked in as she jumped into the water and went after him. He was hypothermic. She swam and pulled him outside to the rocks where she helped him climb out of the water. He had trouble holding on but finally got up. By this time the helicopter had departed scene to refuel, so Jodi was left to provide initial care on scene. When they reached the boat, she covered the hypothermia victim to warm him until they were finally hoisted by the helicopter the next morning.

Jodi was promoted to Chief this year, but she had not benefitted from Master Chief Hill’s advice about water confidence when she decided to become an AST. She claims she wasn’t a fit kid, that she played sports but was a chubby girl—hard to believe looking at her cut biceps and low body fat today. And she was not a strong swimmer. “I was in remedial swim in boot camp,” she says.

Jodi was a Dental Technician at the Air Station Borinquen Medical Clinic in Puerto Rico in 2001, when she decided to make a lifestyle change. “When I got to Puerto Rico, I was at my all-time high weight. I couldn’t get into my uniform dress pants.”

She started working out, improved her fitness, and was in Petaluma, Calif. for EMT training when she went running with an AST there. He suggested that she try AST “A” school. The ASTs back at home noticed her in the gym and encouraged her as well. She put her name on the school list but, worried about criticism, told no one except her clinic doctor. That night, she went to the pool. She made it about halfway across the pool before she reached for the side.

“I thought, I’m an idiot! What was I thinking? But when you’re supposed to do something, it comes together.”

She confessed her swimming deficiency to her clinic doctor. Coincidentally, another doctor, a former Olympic swimmer for Canada, was temporarily assigned to the clinic. For two weeks he took Jodi to the pool and taught her to swim. Two years later, Jodi succeeded in “A” School.

After a couple of years in Los Angeles, Jodi had orders to Kodiak, Ala. when she found out she was pregnant. She didn’t want to burden her fellow ASTs by not carrying her share of the workload, so she continued flying training missions and working hard. When she reported to Kodiak six months pregnant, past the time that she could do any flying, she worried she wouldn’t be accepted by the team. It didn’t take her long to integrate into the shop and she was back in the helicopter and standing duty within three months after her first baby. About six months later, she and her husband decided they would have a second child since her shop could operate with her being out of the aircraft again.

Jodi thought she would relax this pregnancy, but she didn’t. She didn’t fly, but she still exercised aggressively. She was back in Petaluma for EMT refresher training working out with her class when they sprinted up what they call ‘Texas Hill.’ “My competitiveness got the best of me,” she says. She was between three and four months pregnant and the amniotic sac separated from her uterus wall. When she was discharged from the hospital a couple of days later, she was told she would probably miscarry. Out of a self-admitted overdeveloped sense of guilt and commitment, Jodi stayed to finish EMT training, but stopped working out.

When she returned to Kodiak, her Chief sat her behind a desk and she carried to full term. A few years later, when she finally decided to have a third child, she had learned her lesson. “I was fearful. I still worked hard, I still PT’d, but I did this one right. I took my time getting back. This was how it was supposed to go.”

ASTs attend Advanced Helicopter Rescue School (AHRS) in Astoria, Ore., at the mouth of the Colombia River, to practice challenging cliff rescues and swim in heavy surf. “The hard part is getting back to standing duty. I have gone to AHRS every time to get my confidence back.” Since Kodiak, Jodi completed tours in San Diego, Calif., Traverse City, Mich. and is now stationed in Elizabeth City, N.C.

Coast Guard ASTs are driven by their life-saving mission. Their physical and mental conditioning prepares them to brave the most challenging conditions and alter the outcome of Mother Nature’s effects. As Master Chief Hill says, it’s not about whether they’re male or female, “I just want someone who I’m not going to worry about when they get called out at night.” Each of these women has proven herself alongside her male peers through rigorous training, and obstacles at work and at home. They do so out of selfless service, so theirs can be the hands that reach out in the dark to save someone who might otherwise perish.

Martha LaGuardia-Kotite (CAPT, USCG, retired) chronicles the history of the Aviation Survival Technician rating and their heroic exploits, including a chapter dedicated to Kelly Mogk, the first woman in any service to qualify as an aviation rescue swimmer in 1986—whose daring rescue of a Navy fighter pilot solidified women’s credibility in the rate—in her book SO OTHERS MAY LIVE.

Captain LaGuardia-Kotite also wrote CHANGING THE RULES OF ENGAGEMENT, in which she tells the stories of ground-breaking women in the military, including three Women in Aviation Pioneer Hall of Famers: Vice Admiral Vivien Crea, USCG; Colonel Nicole Malachowski, USAF; and U.S. Senator Lieutenant Colonel L. Tammy Duckworth, USA. Visit her website at www.marthakotite.com.